Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

Range Evolution Through Growth and Decay

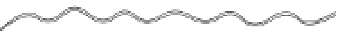

1.2

tectonic flux (

Φ

T

)

11

sediment

yield (

1.0

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0.0

Φ

s

)

22

28

0

10

20

30

40

50

Time (Myr)

maximum macro- and

meso-scale relief

33

44 Myr

A

topographic development

waxing

2

2

1

0 Myr

2

3

44

A'

waning

A

A'

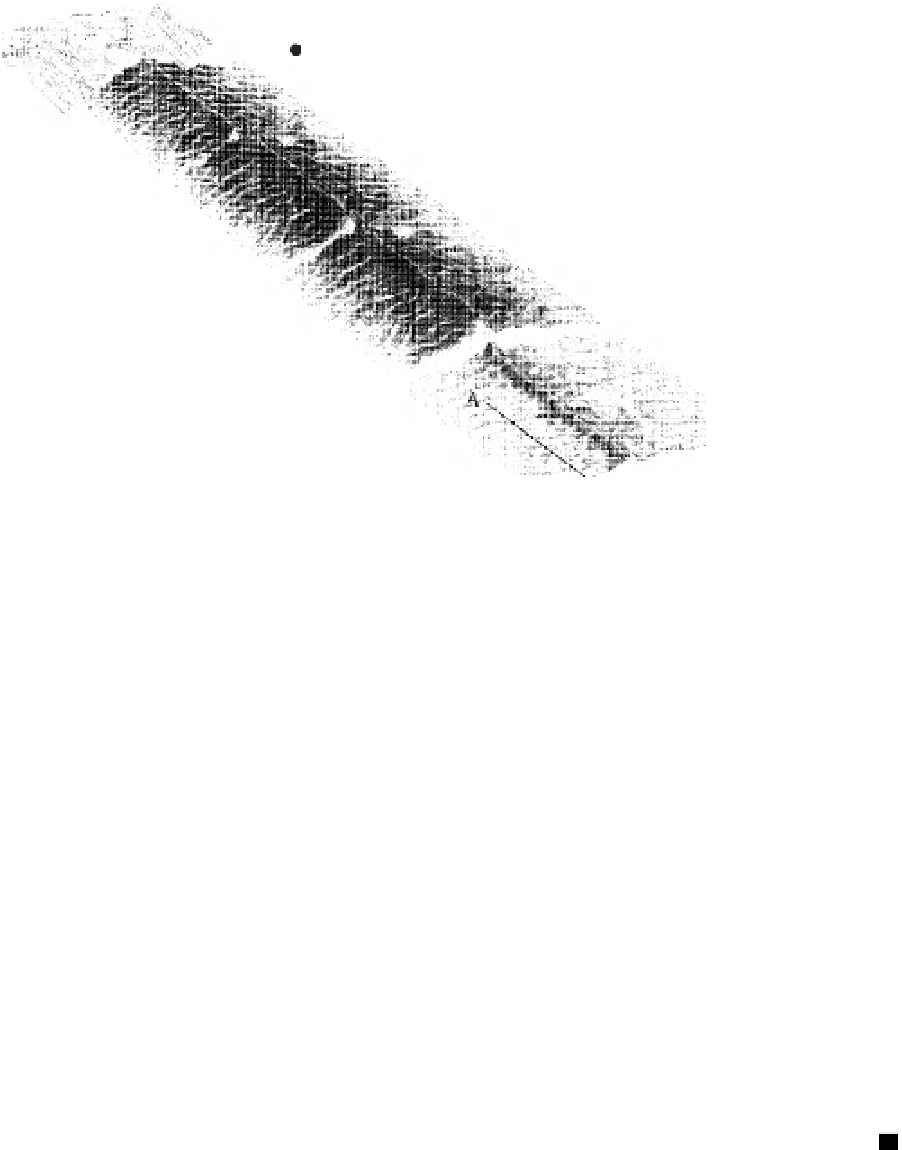

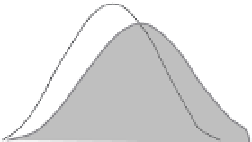

Fig. 11.18

Landscape model incorporating a triangular uplift pattern and a self-forming channel pattern,

showing several snapshots of the landscape as it grows and then decays in relief.

Triangular uplift occurs with the same across-strike pattern, but at different rates in each of the five ages (11, 22, 28,

33, and 44 Myr). The total sediment flux leaving the model landscape lags the rate at which mass is being added by

tectonic forcing, as shown in the inset (top right). A topographic profile (A-A

′

) across the flank of the range depicts

the waxing and waning of relief (bottom left). Modified after Kooi and Beaumont (1996).

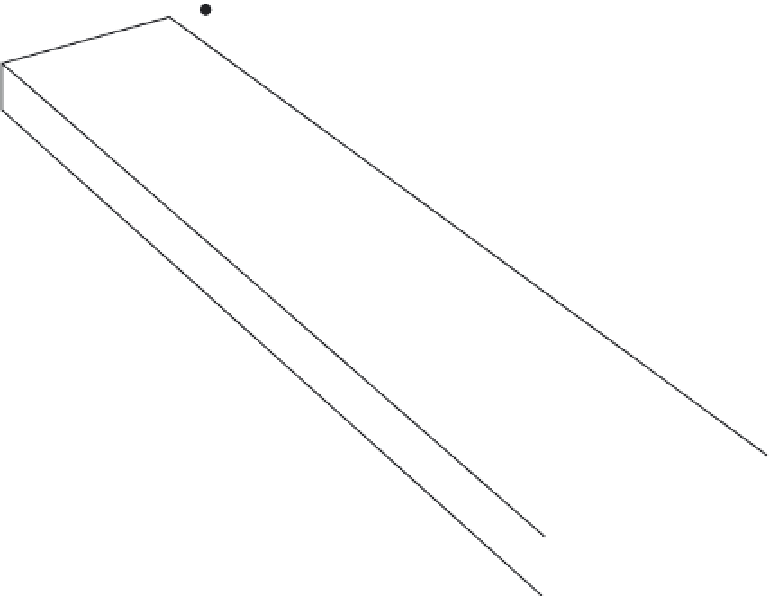

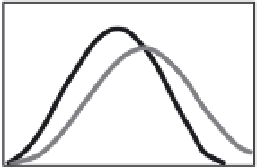

the early square mesh has been replaced with a

Voronoi mesh (an irregular triangular mesh),

which allows more realistic treatment of river

geometries. In Fig. 11.20, we reproduce an

example of the oceanic edge of a landscape

model that is meant to illustrate the differences

between subsiding and uplifting blocks. Modern

landscape evolution models are increasingly

capable of capturing the essence of many

landscape elements, including those that cross

the boundary into the oceanic realm.

In a final example illustrating use of the CHILD

model, we examine a numerical prediction of the

landscape in the frontal zone of Himalayan defor-

mation in western Nepal (Fig. 11.21 and Plate 9).

Here the slip rates on the underlying Main Frontal

Thrust fault are estimated to be

(Fig. 8.21). The Siwalik Hills form above the

southward (leftward) verging Main Frontal Thrust

at the southern margin of the Himalaya, seen in

the background. The Karnali River flows along

the base of the range's backlimb. The mountain-

range model has been run long enough to attain

a steady state in which the form of the topogra-

phy is no longer changing. The asymmetry of the

real topography, and the crenulation of the range

crest are well captured in this model.

Atmospheric interactions

Whereas we all know that the atmosphere

delivers most of the “events” that govern the pat-

terns and the rates of geomorphic processes and

that these patterns reflect the tangling of the

∼

20 mm/yr