Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

Lower Crustal Flow Against A Stro

ng Obstacle

positive pressure

negative pressure

(subsidence)

(uplift)

strong

obstacle

A

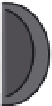

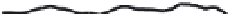

Vertical Deflection versus Effective Elastic Thickness

2500

viscosity = 2 x 10

18

Pa s

velocity = 100 mm/yr

Efective Elastic

Thickne

ss

2000

1500

Te

=

1 km

Fig. 10.48

Impact of a strong crustal

obstacle on lower crustal flow at a plateau

margin.

A. Strong obstacle causes positive pressure on

the upstream side of the flow and negative

pressure on the downstream side, particularly

in comparison to adjacent regions that lack

strong obstacles. B. Upward (downward)

deflection is predicted on the upstream

(downstream) side as a response to the

pressure gradient. The magnitude and

wavelength of deflection depends on

the effective elastic thickness (

T

e

). C. Example

of topographic and deflection profiles across

an inferred strong versus weak (or normal)

margin in eastern Tibet. Both the topography

and deflection mimic that predicted for a

strong obstacle to flow. The inferred “weak”

margin reveals a steadily descending ramp.

Te= 10 km

Te= 30 km

Te= 80 km

1000

positive

pressure

500

0

edge of obstacle

-500

B

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

1400 1600

1800 2000

Distance (km)

C

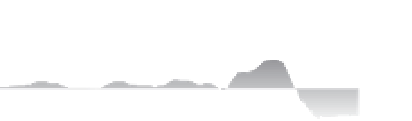

Eastern Tibet - Sichuan Basin Topography

West

East

strong margin

dynamic

topography

weak margin

weak margin

strong margin

edge of

Sichuan Bas

i

n

Eastern Tibetan Plateau

West

East

Distance

and vice versa (Fig. 10.49). Fourth, where

surface erosion at the plateau margin is intense,

the ductile, lower crustal channel could be

drawn toward the surface (Fig. 1.9C) and active

faults would likely bound such a channel

(Beaumont

et al

., 2001). Conversely, with less

intense erosion, surface faulting might be sig-

nificantly reduced, and the ductile lower crust

could remain deeply buried, despite a strong

topographic gradient across the plateau's

margin.

Many of these characteristics are observed

along the eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau

(Clark and Royden, 2000; Royden

et al

., 1997).

From the southeastern corner of Tibet, a huge,

low-gradient ramp extends south and east to

the lowlands (Fig. 10.50). North of the Sichuan

Basin, a second ramp extends towards the

northeast. These two ramps are interpreted as

zones in which lower crustal flow is channeled

outward from the Tibetan Plateau. In between

these ramps, the Sichuan Basin appears to be

underlain by old, stiff crust that resists the

interpreted outward flow of lower crust from

beneath Tibet (Clark

et al

., 2005a). As suggested

by topographic profiles (Fig. 10.48C), the pla-

teau surface appears deflected upwards adjacent

to this more rigid Sichuan crust. In comparison

to the Himalayan front, erosion is generally

slower in eastern Tibet, and active surface fault-

ing is considerably more subdued, although cer-

tainly is not absent - as demonstrated by the

2008

M

=

7.9 Wenchuan earthquake (Kirby

et al

.,

2008). The inferred pattern of outward crustal