Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

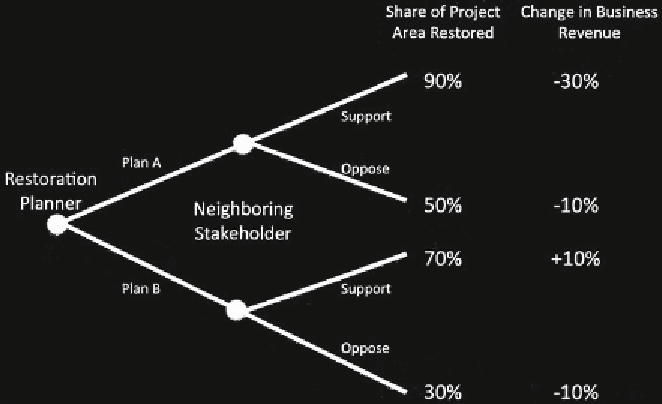

FIGURE 17.1.

Example decision tree by a restoration planner between two plans (A or B) fol-

lowed by a decision of a neighboring stakeholder to support or oppose the restoration plan.

The outcome payoff for the restoration planner is shown in terms of total area or function re-

stored, whereas the payoffs to the stakeholder are represented by change in the stakeholder's

revenue. While the highest share of restoration is possible under Plan A, the stakeholder will

oppose Plan A because the stakeholder expects less total loss. Plan B, which would be unop-

posed, would actually lead to a greater share of restoration than a choice of Plan A.

each individual acting in his or her own self-interest, based on expecting that everyone

else is doing so as well.

One can envision a scenario described in figure 17.1 using the example of a farmer

(as the stakeholder) and restorationist on the Sacramento River, briefly described ear-

lier. For example, the restorationist's preferred choice might be to plant many species

of tree seedlings densely to achieve the greatest success in restoring a riparian forest

ecosystem, which was the dominant ecosystem in this region prior to extensive agri-

culture (Vaghti and Greco 2007). But this action might substantially increase the

farmer's expectations of flooding on his lands (Buckley 2007). This could lead farmers

to engage in the local political process to block the restoration entirely. As a compro-

mise, the restorationist might plant trees less densely mixed with native grasses creat-

ing more of a savanna habitat, which would have minimal impacts on flooding (Ef-

seaff et al. 2003; Golet et al. 2009), and might also provide habitat for beneficial

insects, which could control insect damage to farmers' crops. Savannas were likely

historically patchily distributed in this region in locations with shallow soils.

The reasoning in the backward-induction process might seem natural and recog-

nizable as part of strategic thinking in games, such as chess, or even as part of a bar-

gaining or compromise process. You look at your options and imagine what others will

subsequently decide given the scenario you leave them with. The more rounds of de-

cisions the more difficult and the less certainty you are likely to have for your guess,

but these uncertainties can be factored into your decision probabilistically. These