Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

25

20

15

10

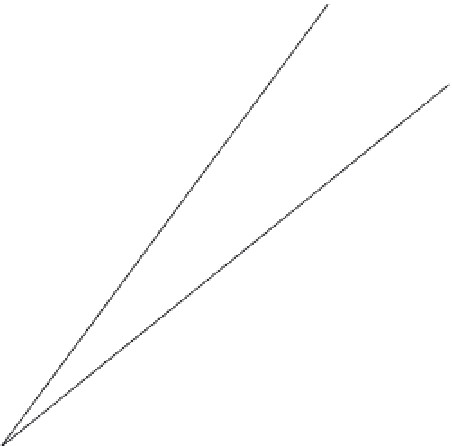

Fig. 4.6

Expected prediction and

uncertainty intervals vs. the predicted

value from the RHEM model. Expected

values were computed as the mean

of 1000 model runs, providing

randomly generated values for each

model parameter to compare with

predicted soil loss from three sample

storms at three separate locations

(after Wei

et al

., 2008).

5

Expected value

Lower uncertainty interval

Upper uncertainty interval

0

0

5

10

15

20

25

Predicted soil loss (kg/m

2

)

Section 4.5 has reviewed a wide range of ways

in which model developers have attempted to

describe model sensitivity, and the error or

uncertainty associated with erosion model pre-

dictions. All of these approaches demonstrate

some merit, although none can be described as a

holistic treatment of model uncertainty by quan-

tifying both input uncertainty (through parame-

terization and parameter interactions) and model

structural uncertainty: the dominant sources of

epistemic uncertainty discussed in Section 4.4.

In addition, few models have been adequately

evaluated against observed data, to demonstrate

how well predictions relate to real-world obser-

vations or to show how well observations are

captured within uncertainty bounds. The fol-

lowing section summarizes an attempt to deal

with these problems by using the GLUE approach

to evaluate the WEPP model against data from

both the UK and the US (Brazier

et al

., 2000).

Although it is by no means a complete assess-

ment of model uncertainty, it serves as a good

example of what can be done to assess the qual-

ity of model predictions, and to understand the

sources of model uncertainty which may help

model developers to constrain uncertainty in

future model development.

4.6

Case Study: Using WEPP to Predict

UK and US Erosion Data

Many papers have been written describing the

WEPP model and its applications (more than 100

to date), yet very few (as reviewed above) have

attempted to evaluate the uncertainty associated

with model predictions. If process-based soil ero-

sion models proliferate, in the same manner as

their forebears, the USLE family of models, and

this proliferation is not accompanied by assess-

ment of predictive uncertainty, then the field of

erosion modelling will not move forward in terms

of reducing this predictive uncertainty - a sce-

nario that is undesirable for both model develop-

ers and model users alike.

The WEPP model was analysed by Brazier

et al

. (2000) against data that were collected in

large plot-scale experiments in both the UK, at

the Woburn Erosion Reference Experiment (Catt

et al

., 1994), and the US, at the Holly Springs