Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

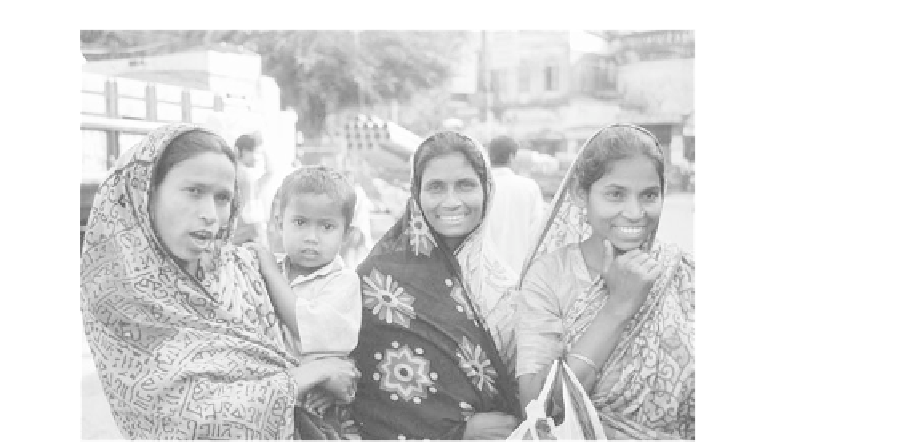

Figure 9-7

Bangladeshi women. Self-help programs are

improving the lives of many women in Bangladesh.

These women are middle class.

Photo courtesy of

B. A. Weightman

.

and craft and other cooperatives have markedly advanced

living standards for some Bangladeshi women.

Bangladesh' s population dilemmas derive more from

distribution than from sheer numbers. Rural-to-urban mi-

gration has overwhelmed cities, especially Dhaka and

Chittagong. In 1961, a mere 5 percent of Bangladeshis lived

in cities. In 1991 it was 18 percent. Currently , 25 percent

live in urban places, and by 2015 that will increase to

37percent. In other words, 80 million Bangladeshis will

be urban residents by 2020. This is an amazing number in

the context of infrastructural requirements.

Take power availability as an example. Only 16 per-

cent of Bangladeshis have access to electricity . The coun-

try often faces riots over blackouts. At the opening of the

largest generating plant, 30 miles (50 km) northwest of

Dhaka, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina urged people to

save electricity at home and at work by shutting off

lights. Public and private sector projects were expected

to boost the national grid' s power to 4,700 megawatts by

2002. But there is another problem: People tap into power

lines illegally , and nearly 30 percent of power production

is lost to theft.

Poor migrants typically end up living in slums, squatter

settlements, or as pavement dwellers. There are already

about 25 million of these individuals, more males than

females.

Dhaka, the country' s capital and primate city , attracts

the most migrants. In 1992, Dhaka had 7.4 million in-

habitants. It now has 10 million. By 2015, it is expected

to have 17 million residents, with at least 50 percent

living in slums or worse. Dhaka' s Old City can only be

described as a hive of humanity (Figure 9-8).

Every crumbling building, room, cubicle, alley ,

doorway , and indentation reveals people living in every

imaginable condition. The narrow streets are crammed

with people, carts, bicycle rickshaws, trucks, and buses,

all carrying stupendous loads of oil drums, cotton bales,

vegetables, sacks of ice, sheets of metal, thousands of

rubber thongs (flip-flops), and baskets of poultry . The

city is a limitless kaleidoscope of colors, sounds, and

smells.

Child labor is common. This is reflected in the fact

that only 20 percent of slum children attend school. In

addition, at least one-third of slum dwellers are sick at

any one time. Slum communities have the highest infant

and maternal mortality rates in the nation, in part

because health-care programs have been geared to rural

as well as more affluent urban areas.

Outside Dhaka' s Old City are still relatively old areas

that are becoming increasingly densified. Here, unchecked

settlement outpaces government efforts to develop housing

and other infrastructural needs. Incentives to decentralize

and create communities outside the city have met with

limited success.

Dilemmas of Growth

CONDITIONS IN THE CITIES

Rural push factors drive urban migration streams while

growth in production is not expected to meet employ-

ment needs. As population experts Professor Abdul

Barkat, U. R. Mati, and M. L. Bose (1997) point out, “ur-

banization in Bangladesh will remain poverty-driven.”

Search WWH ::

Custom Search