Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

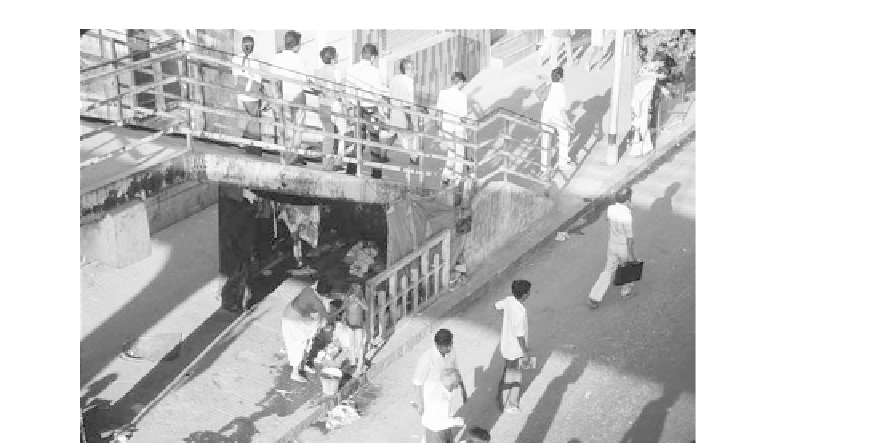

Figure 4-7

This family lives under a pedestrian overpass over

a railroad line in Mumbai. This is an excellent

location as it is sheltered and near a public

“standpipe”—a water tap. Also, the family can

scavenge the tracks for food such as banana skins

that are thrown out of the train windows by mid-

dle-class commuters.

Photograph courtesy of

B. A. Weightman.

8 percent of Manila' s slum residents remain uncounted.

Moreover, slum populations do not include millions of

pavement-dwellers who have no permanent home at

all. Entire families, mostly in South Asia, seek shelter in

railroad stations, under overpasses, in doorways, in

parks, in alleys, or they simply lie down on the sidewalk

(Figure 4-7).

Slum space has become commodified. For instance,

the majority of slum dwellers in Bangkok actually rent

the land where they build their shacks. In India, people

who prop their shanties against high-rise apartment

blocks pay rent to building or apartment owners. Land-

lordism is a fundamental and divisive social relation in

the slum world. Already-poor slum dwellers rent to

poorer slum dwellers and have no qualms about ousting

those who can't pay . Even pavement-dwellers must pay

someone for their space.

Slum communities continue to grow in scope and ex-

tent although most governments have tried to get rid of

them. Consequently , there is a never-ending social war

against the urban poor in the name of “beautification,”

and even “social justice for the poor.” Persistent slum-

clearance operations in Delhi, designed to create space for

middle-class subdivisions, have produced endless cycles

of settlement, eviction, demolition, and resettlement.

The most intense battle occurs in downtowns and

major urban nodes. Globalized property values collide

with the desperate need of the poor to be near central

sources of income. Officials may redraw spatial bound-

aries to the advantage of landowners, foreign investors,

elite homeowners, and middle-class consumers. The

urban poor are a type of nomad—transient in a perpetual

state of relocation.

Some cities such as Mumbai and Delhi have built

satellite cities to encourage the poor to move from more

valuable land nearer to the city centers. These new , per-

ceptibly advantageous locations have emerged as magnets

for rural-urban migrants and middle-class commuters.

Squatters, renters, and even low-level landlords are sum-

marily evicted without compensation or right of appeal.

It is poor city dwellers that many elite and middle-

class groups consider to be the population “them,”

“those people,” “the problem.” Or they deny their exis-

tence altogether. (This attitude is confirmed by several

Indian authors.)

I once had an Indian student in my Geography of

Asia class who insisted that there was no poverty in

India. When Geeta saw my slides she was appalled and

couldn't believe what she was witnessing. She told me

that she only left her (rich) family compound in Delhi in

a chauffeured limousine with its windows blackened to

keep “them” from looking in. The bulk of her outings

were to private school, fancy malls, or social functions in

luxury hotels. After a semester break back in Delhi,

Geeta came to see me. She told me that she had never re-

ally looked at the landscape around her and that once she

realized some of its realities, she tried to talk about them

with her parents. Her mother told her that, “We don't

discuss such things.”

WHO considers road traffic one of the worst health

hazards facing the urban poor and predicts that road

accidents will be the third leading cause of death by

Search WWH ::

Custom Search