Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

M

ARITIME

VS

. C

ONTINENTAL

I

NFLUENCE

T

OPOGRAPHIC

V

ARIATION

Large bodies of water, especially the oceans, greatly

affect the temperature of adjacent landmasses. Because

water reflects a larger proportion of insolation in relation

to land and loses heat readily through surface evapora-

tion, it has a high specific heat, and readily mixes layers

vertically; the temperature of large bodies of water is

slower to change than that of landmasses. Land heats up

more during the summer because all the absorbed heat

stays in the surface horizon and the atmosphere close to

that surface, and it cools to a lower temperature during

the winter because of reradiation and heat loss. Water

masses are, therefore, moderators of broad fluctuation in

temperature, tending to lower temperatures in the sum-

mer and to raise temperatures in the winter. This water-

or marine-mediated effect on temperature is called a

maritime influence

, in contrast to the more widely fluc-

tuating variations in temperature encountered at a dis-

tance from water under a

continental influence

. Maritime

influences help create the unique Mediterranean climates

of such places as coastal California and Chile, where

nearby upwelling cold currents accentuate the moderat-

ing influences during the dry summer season.

Slope orientation and topography introduce variation in

temperature as well, especially at the local level. For

example, slopes that face toward the sun as a result of the

inclination of the earth on its axis experience more solar

gain, especially in the winter months. Hence, an equator-

facing slope is significantly warmer than a pole-facing

slope — all other factors being equal — and offers unique

microclimates for crop management.

Valleys surrounded by mountain slopes create unique

microclimates as well. In many parts of the world, air that

moves downslope due to winds or pressure differences

can rapidly expand and heat up as it descends — a process

known as catabatic warming. (The wind associated with

this phenomenon will be discussed in Chapter 7.) As the

air is warmed, its ability to hold moisture in vapor form

(relative humidity) goes up, increasing the evaporative

potential of the warmer air.

Valleys are subject to nighttime microclimate varia-

tion as well. On the higher elevation slopes above a

valley, reradiation occurs more rapidly; since the cooled

air that results is heavier than the warmer air below, the

cooler air begins to flow downslope — a phenomenon

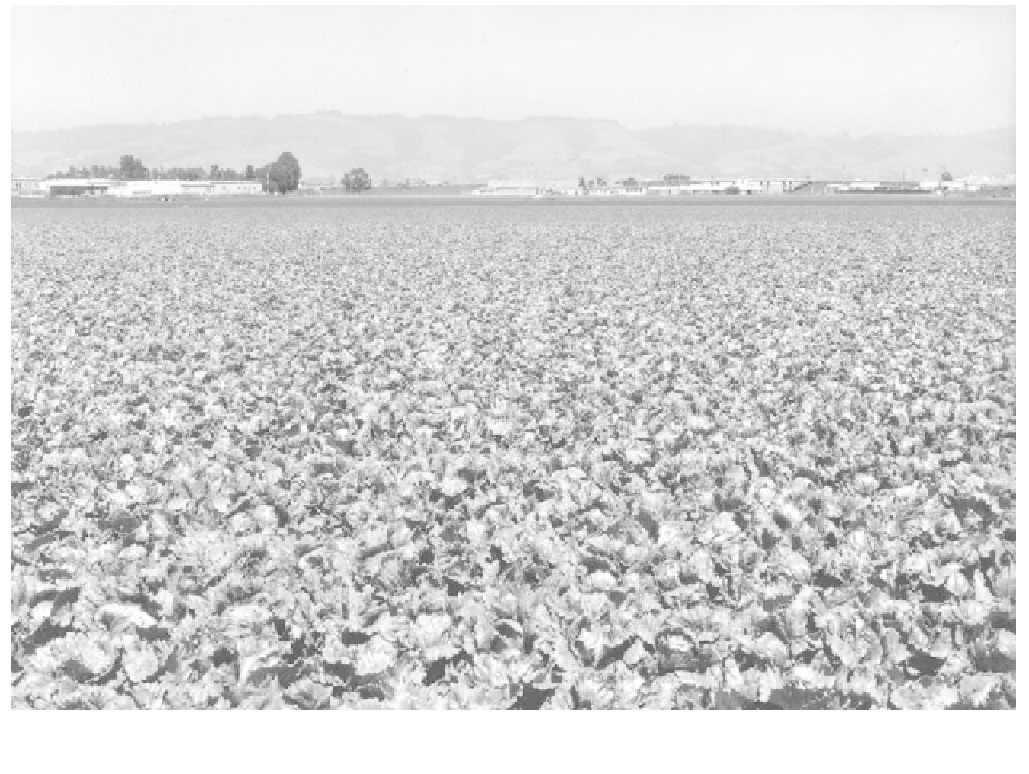

FIGURE 5.3

Lettuce grown year-round in a temperate maritime climate.

Cooling summer fog and the warming effect of the

nearby ocean in the winter permit year-round vegetable and fruit production on the central coast of California.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search