Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

is harnessed and affected by the process. A number of

researchers have developed theoretical models that help

us conceptualize these complex relationships. These mod-

els offer alternative conceptions of how agroecosystems

exist in the intersection between nature and society —

how they come about and change as a result of a complex

interaction between ecological and social/economic fac-

tors. And each model suggests particular requirements for

sustainability. Three of these models are presented below.

In the 1970s, when agriculture was dominated by

Green Revolution thinking and most farmers and research-

ers were ignoring both the ecological basis of agriculture

and its social ramifications, the Mexican agronomist and

ethnobotanist Efraím Hernandéz Xolocotzi introduced a

model that pictured agroecosystems as the outcome of

constant coevolution between ecological, technological,

and socioeconomic factors (Figure 24.4). Each factor

influences the design and management of the agroecosys-

tem while simultaneously interacting with the others. A

complex set of feedbacks between factors and influences

shapes the agroecosystem over time. Implicit in this model

is the notion of balance, and imbalance becomes a matter

of concern and a barrier to sustainability. For example, if

market demands (a socioeconomic factor) cause farmers

to put irrigation (a technological factor) into place so that

limited rainfall (an ecological factor) can be ignored, the

system can be thrown out of balance. The factor interac-

tion may be confined to a back and forth interplay between

socioeconomic pressures and technological fixes, and

ecological sustainability is sacrificed.

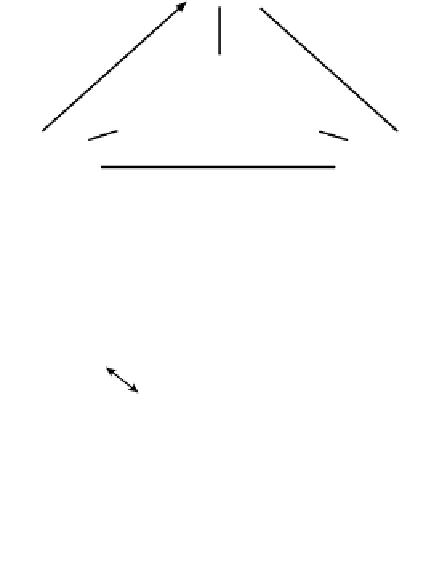

Cornelia Flora offers a model focused on the rural

communities in which agricultural production is based. In

her model (Figure 24.5), agroecosystems come about as

human communities use the potential of the local landscape

to extract value and maintain themselves. In this process,

they use four basic types of resources. Since these basic

resource types are used to create new resources, she defines

them as forms of capital. As with the Hernandez X. model,

balance is required for sustainability. Specifically, all four

forms of capital must be constantly replenished, not

depleted. For example, a strategy that emphasizes the short-

term accumulation of financial capital through intensive

irrigated agriculture can decrease natural capital by causing

salinization or loss of natural wetlands.

From the perspective of environmental sociology, Gra-

ham Woodgate proposes a model in which nature (the

ecological foundation of agroecosystems) is wholly

enclosed within society, and the relationship between the

two recalls the coevolution of Herndandez X.'s model. In

this model, agroecosystems — which occupy the interface

Ecological

factors

Agroecosystem

Socio-economic

factors

Technological

factors

FIGURE 24.4

Efraím Hernandéz Xolocotzi's model of the factors influencing the design and management of agroecosytems.

[Modified from Hernandez Xolocotzi, E. (ed.) 1977.

Agroecosistemas de México: Contribucciones a la Enseñanza, Investigación, y

Divulgación Agrícola

. Colegio de Postgraduados: Chapingo, México.]

Human

Capital

Social

Capital

Communities

healthy ecosystems

vital economy

social equity

Financial/

built

Capital

Natural

Capital

FIGURE 24.5

Cornelia Flora's model of agroecosystems as products of human communities mediated by factors conceived

as varying forms of capital.

[Modified from Flora, C. ed., 2001.

Interactions between Agroecosystems and Rural Communities

.

Advances in Agroecology. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL.]

Search WWH ::

Custom Search