Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

Changes in vegetation

and built structures

New woody vegetation

New structures

1945

2002

Terrain

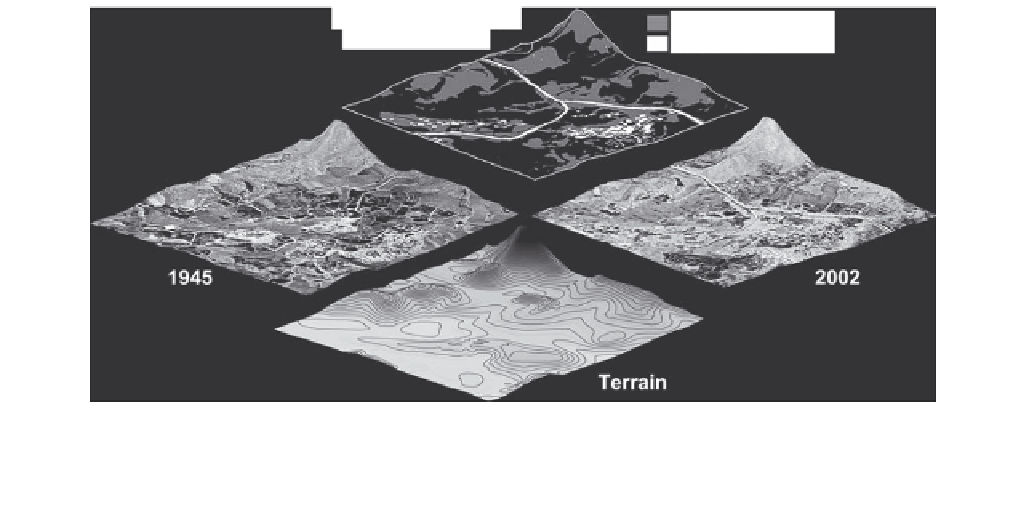

FIGURE 22.3

GIS analysis of a 1 km

2

area in western Guangdong Province, China (Dianbai County) showing changes in the

agricultural landscape over time.

In the transition from a traditional to a more industrialized economy, built structures increased,

much agricultural land was abandoned, and woody vegetation — previously been burned and harvested for fuel — recovered in

formerly agricultural areas and in the hills. Images and data courtesy of Erle C. Ellis (www.ecotope.org for more information).

in many formerly agricultural lands, built structures

increased. As the images in Figure 22.3 indicate, multiple

layers of data that vary in content and time can be inte-

grated to understand the drivers and consequences of

changes such as these.

Knowledge of the farming practices that have been

used in the past in any particular landscape, combined

with knowledge of how different components of the land-

scape interact, makes it possible to understand how farm-

ing practices impact the nonfarm elements of a landscape,

and vice versa. Soil erosion rates, fertilizer inputs, pesti-

cide applications, irrigation, crop types and diversity, and

other practices and processes can be understood in terms

of landscape patterns. Based on this knowledge, recommen-

dations for change in either cropping patterns or farming

practices can be made, and decisions on agroecosystem

design can move beyond the farm and into the larger

landscape context.

many different stakeholders in an agricultural area (different

farmers, governmental agencies, conservation interests,

etc.). Its essence is the inclusion of natural ecosystems and

local biodiversity in management decisions and planning.

Thus, landscape-level management can be implemented by

an individual farmer who has direct control over only a small

part of the agricultural landscape of a region.

The implementation of landscape-level management

has two guiding principles:

1.

Diversify the agricultural landscape by increas-

ing the density, size, abundance, variety of non-

crop habitat patches, and by creating more

connections between them. These patches can

vary in their level of disturbance and “natural-

ness;” what they share in common is the ability

to be sites where natural ecological processes

can occur and where native or beneficial plant

and animal species can find suitable habitat.

2.

Manage cropping areas to reduce their negative

impacts on the natural environment and maxi-

mize their value as habitat for native species.

This means eliminating or reducing the use of

pesticides, inorganic fertilizer, and irrigation,

and finding alternatives to farming practices

that interfere with ecosystem processes, such as

frequent tilling, leaving fields without soil

cover for long periods, planting large-scale

monocultures, and mowing or spraying road-

sides and ditches.

MANAGEMENT AT THE LEVEL OF THE

LANDSCAPE

When agroecosystem management is carried out at the

level of the larger agricultural landscape, the antagonism

that so often exists between the interests of natural ecosys-

tems and those of managed production systems can be

replaced by a relationship of mutual benefit. Natural and

seminatural ecosystem patches included in the landscape

can become a resource for agroecosystems, and agroeco-

systems can begin to assume a positive rather than negative

role in preserving the integrity of natural ecosystems.

The concept of landscape-level management does

not necessarily mean coordinated management among the

The latter principle goes hand-in-hand with everything

discussed in this text up to this point. Reducing nonfarm

Search WWH ::

Custom Search