Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

WHY CONVENTIONAL AGRICULTURE IS

NOT SUSTAINABLE

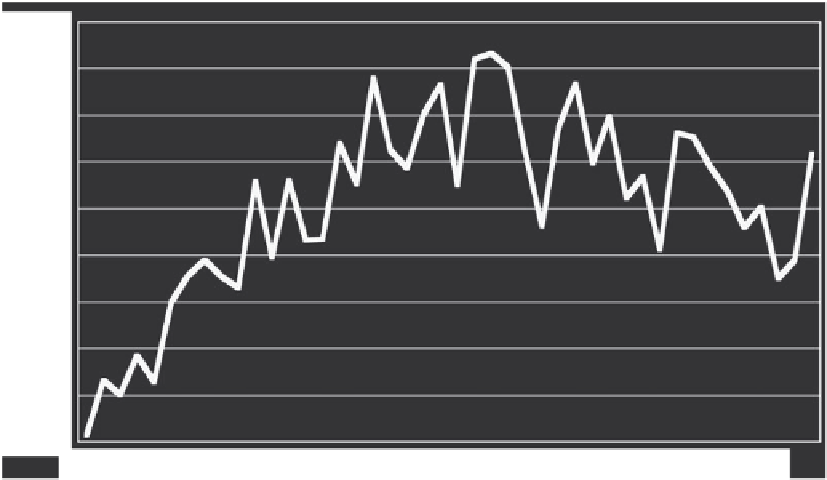

grains has trended downward since reaching a peak in

1984. This situation is the result of reduced annual yield

increases combined with continued logarithmic popula-

tion growth.

The ways in which conventional agriculture puts

future productivity at risk are many. Agricultural resources

such as soil, water, and genetic diversity are overdrawn

and degraded, global ecological processes on which

agriculture ultimately depends are altered, human health

suffers, and the social conditions conducive to resource

conservation are weakened and dismantled. In economic

terms, these adverse impacts are called

externalized costs

.

They are real and serious, but because their consequences

can be temporarily ignored or absorbed by society in gen-

eral, they are excluded from the cost-benefit calculus that

allows conventional agricultural operations to continue to

make economic “sense.”

The practices of conventional agriculture all tend to com-

promise future productivity in favor of high productivity

in the present. Therefore, signs that the conditions nec-

essary to sustain production are being eroded should be

increasingly apparent over time. Today, there is in fact

a growing body of evidence that this erosion is underway.

In the last 15 years, for example, all countries in which

Green Revolution practices were adopted at a large scale

have experienced declines in the annual growth rate of

the agricultural sector. Further, in many areas where

modern practices were instituted for growing grain in the

1960s (improved seeds, monoculture, and fertilizer

application), yields have begun to level off and have even

decreased following the initial spectacular improvements

in yield. Mexico, for example, has seen little change in wheat

yields since 1980, after climbing from about 0.9 tons/ha in

1950 to 4.4 tons in 1982 (Brown, 2001). For the world

as a whole, the rise in land productivity has slowed

markedly since about 1990. In the 40 years before 1990,

world grain yield per hectare rose an average of 2.1% a

year, but between 1900 and 2000, the annual gain was

only 1.1 percent (Brown, 2001). From 2000 to 2003,

global grain reserves shrank alarmingly every year, from

635 million tons (a 121-d supply), to 382 million tons

(a 71-d supply).

Figure 1.4 shows the world's annual per capita grain

production for each year from 1961 to 2004, as calculated

by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the

United Nations. These data indicate that after trending

upward for many years, per capita production of cereal

S

OIL

D

EGRADATION

Every year, according to the Food and Agriculture Orga-

nization of the United Nations, between 5 and 7 million

ha of valuable agricultural land are lost to soil degrada-

tion. Other estimates run as high as 10 million ha per

year (e.g., World Congress on Conservation Agriculture,

2001). Degradation of soil can involve salting, waterlog-

ging, compaction, contamination by pesticides, decline

in the quality of soil structure, loss of fertility, and ero-

sion by wind and water. Although all these forms of soil

degradation are severe problems, erosion is the most

widespread. Worldwide, 25,000 million tons of topsoil

are washed away annually (Loftas et al., 1995). Soil is lost

to wind and water erosion at the rate of 5 to 10 tons/ha

350

340

330

320

310

300

290

280

270

260

1961

1965

1969

1973

1977

1981

1985

1989

1993

1997

2001

FIGURE 1.4

Worldwide grain production per capita, 1961 to 2004.

Data source

: Food and Agricultural Organization, FAOSTAT

database; Worldwatch Institute.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search