Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

during a rainless summer or cold winter, systems developed

whereby the pasture biomass was harvested, dried, and

stored for feed to be used during the time of scarcity, at

which time the animals were often kept in confinement.

Such pasture systems are still very common today all

over the world. Many agricultural universities and colleges

have entire departments and programs devoted to the study

of pasture design, management, and improvement, espe-

cially where animal production systems are most prevalent.

M

IXED

C

ROP

-L

IVESTOCK

S

YSTEMS

While the coevolution of animals and forage plants was

taking place, humans in some parts of the world were also

developing crops for their own consumption. Animals

were nearly always part of this crop development, since

they provided the cultivation and transport power, as well

as manures for fertilization of crops, and played a part in

the diversification of farm landscapes that must have come

about as humans balanced the needs of themselves, their

animals, and the environment upon which both depended.

All early agricultural societies employed domesticated

animals to some extent. Ancient cultures in the Indus

Valley domesticated the chicken. The cultures of South-

east Asia raised fowl and water buffalo. In Mesopotamia,

cattle, sheep, and goats were important. Even in the New

World, where domesticable wild species were less abun-

dant, domesticated animals such as the turkey and hairless

dog played important roles in agricultural societies. The

Anasazi of the American Southwest, for example, grew

corn, beans, and squash, but raised domesticated turkeys

for feathers, emergency food, and fertilizer (Figure 19.6).

The degree of integration of plants and animals varied

in early agricultural systems. In some societies, crop

production systems developed alongside livestock pasture

systems; in other cases, food derived from animal domes-

ticates supplemented a crop-based system. Either way, the

pattern was set for integrated crop-livestock systems to

develop along with the major centers of human civilization.

These integrated systems involved a diverse mixture

of different activities, managed together as a working

whole to take advantage of the ecological complementa-

rity of each component or enterprise. In many temperate

parts of the world with adequate rainfall, including the

Middle East, Europe, northern Africa, and southern Asia,

integrated systems reached a level of considerable com-

plexity. In early modern Europe, for example, a typical

integrated farm had pasture for harvestable feed or forage

(annual and perennial), crops (annuals and perennials),

animal grazing areas (with some possible improvement

in plant species used as forage), corrals, forest or woodlot,

often some sort of wetland, stream or well, and places

for human habitation and activity, along with rotations

and fallows involving multiple combinations of each

component.

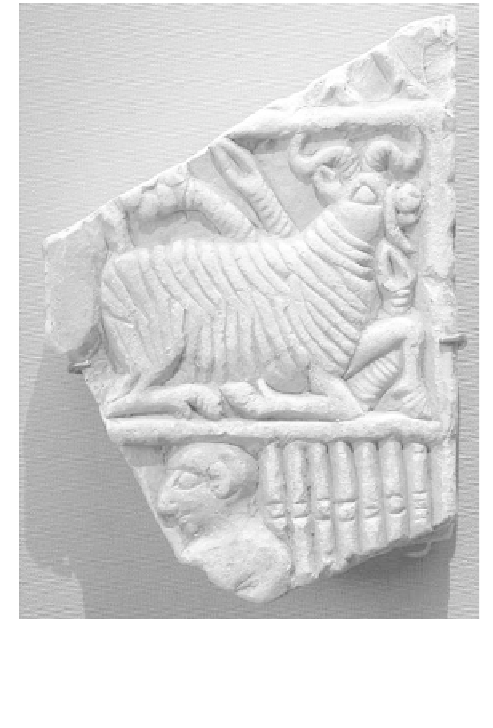

FIGURE 19.6

Domesticated sheep in ancient Mesopotamia.

Domesticated animals, such as the sheep depicted on this frag-

ment of a stone carving in The Louvre, were important in the

early form of agriculture practiced in the “fertile crescent.”

This style of integrated farm — and the associated

cultural values of animal husbandry — was imported to

the U.S., where it became the model system. Until the

beginning of the 20

th

Century, most farms in the U.S.

showed this integration of multiple enterprises. Integrated

farms still exist today, but they are greatly outnumbered

by specialized and industrial-scale operations that com-

pletely separate livestock and crop production.

The disintegration of livestock and crops came about

with the widespread introduction of specialized machin-

ery, fertilizers, and pesticides following World War II,

but specialization in U.S. agriculture began many

decades before that (Gregson, 1996). In order to respond

to uniform market signals and distant markets, farmers

began to rely on production inputs that had the effect of

standardizing both growing conditions and response to

management and climate. Diversity seemed to be less

necessary, and farms began to simplify. Ready access to

effective and cheap chemical fertilizers encouraged the

perception that farmers no longer had to depend on bio-

logical nitrogen fixation and nutrient recycling through

livestock to maintain soil health. Government support

programs and academic research institutions further

promoted the value of specialization, and by the end of

the 1980s, the separation of livestock and crops was

fairly complete (Gregson, 1996).

Search WWH ::

Custom Search