Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

USING FLOWERING PLANT CORRIDORS TO INCREASE BENEFICIAL INSECT DIVERSITY IN

A VINEYARD

In many of the grape-growing regions of California, large-scale monoculture vineyards dominate the landscape.

The numbers of natural insect predators and parasitoids that might otherwise exist in these landscapes are greatly

reduced because of the relative lack of important food resources and overwintering sites offered by natural and

noncrop vegetation.

In contrast, where viticulturalists have retained or created a more diverse landscape by keeping vineyards smaller

and maintaining natural vegetation patches and riparian corridors at vineyard perimeters, they have encouraged the

presence of natural predators and parasitoids. The positive effect of landscape diversification practices in increasing

the diversity of beneficial insects has been demonstrated in a variety of agroecosystems (Altieri 1994a; Coombes

and Sotherton 1986; Corbett and Plant 1993; Thomas, Wratter, and Sotherton 1991).

In these more diverse viticultural areas, where strips and patches of natural and other noncrop vegetation are

interspersed among monoculture vineyards, analysis of the dynamics of insect predator and herbivore populations

is a good application of island biogeography theory. The grape monocultures in these landscapes are “islands” in

the sense that beneficial insects don't live in them year-round but instead disperse into them from the adjacent

noncrop vegetation when their prey and hosts are present.

A study by Clara Nicholls, Michael Parrella, and Miguel A. Altieri (2000) has shown that where noncrop

vegetation already exists adjacent to a vineyard, its positive effect on beneficial insect biodiversity can be greatly

enhanced by a relatively simple practice: penetrate the vineyard with corridors of flowering plants contiguous with

the adjacent natural vegetation. The corridors serve beneficials both as a habitat and a “biological highway,” allowing

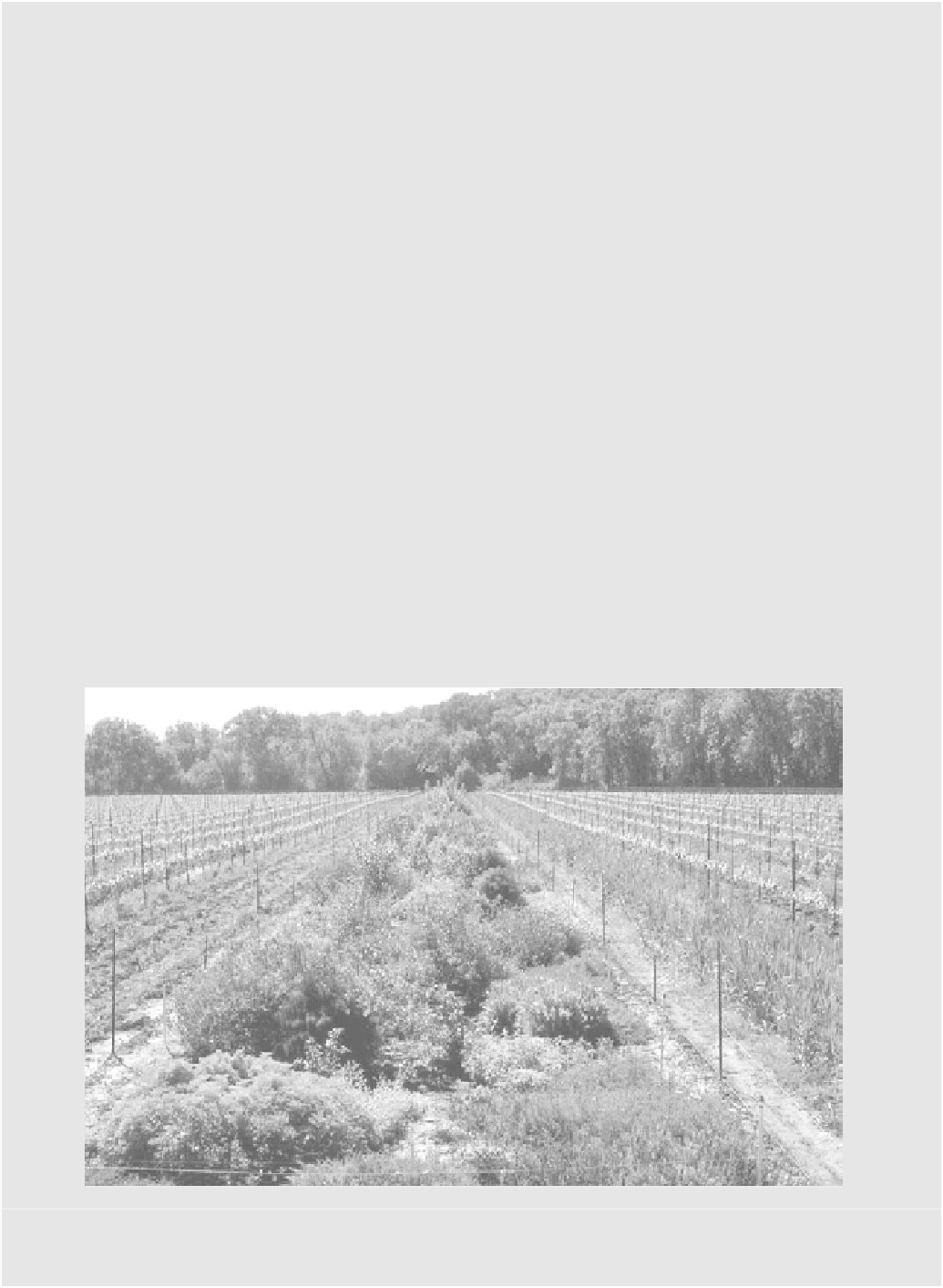

them to move from their refugia in nonagricultural areas deep into the vineyard (Figure 16.7).

The researchers compared two adjacent vineyard blocks that differed in only one respect: block A was bisected

by a 600-meter-long corridor of noncrop vegetation contiguous with a bordering riparian forest; block B had the

bordering forest but no analogous corridor. The corridor in block A supported 65 species of locally adapted flowering

plants, including fennel (

Foeniculum vulgare

), yarrow (

Achillea millefolium

), daisy fleabane (

Erigeron annuus

), and

butterfly bush (

Buddleia

spp.). Most of these plants were nonnative but not particularly weedy (an exception is

fennel; care should be taken in using it for such corridors).

FIGURE 16.7

Corridor of flowering plants penetrating the interior of a vineyard in California.

The corridor facilitates

the movement of beneficial insects into the vineyard from their refugia in the riparian forest (in the background).

Search WWH ::

Custom Search