Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

N

2

N

0

N

1

14

INTERFERENCE

Grass

Clover

12

N

2

Addition impact

Removal impact

10

N

0

= no N fertilizer

N

1

= 7.5 g N /m

2

N

2

= 22.5 g N /m

2

N

0

N

1

•

Competition

•

Parasitism

•

Herbivory

8

•

Allelopathy

•

Food source for

beneficials

N

1

Yield

(g / dm

2

)

N

0

N

2

6

N

1

N

2

N

0

4

N

1

N

2

Combined removal and addition

N

0

2

0

•

Mutualisms

•

Microhabitat midification

67

84

99

113

133

Days after sowing

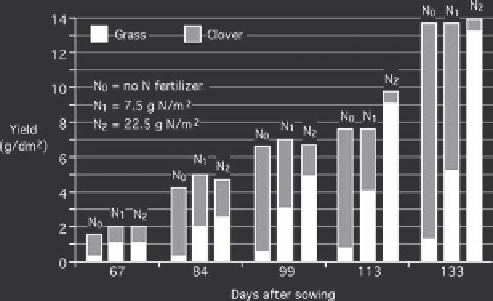

FIGURE 15.2

Relative dominance of grass (Lolium rigidum)

and clover (Trifolium subterraneum) in relation to levels of nitro-

gen fertilizer.

(Stern, W. R. and C. M. Donald. 1961.

Australian

Journal of Agricultural Research

13: 599-614. With permission.)

FIGURE 15.1

Modes of interference underlying species

interactions in communities.

combined addition/removal interference between popula-

tions may modify the microclimate of a cropping system

in ways that affect populations of other species. Shading,

soil insulation, temperature and wind modification, and

altered moisture relations can combine to create a micro-

climate within the cropping system that is conducive to

the presence of organisms that are beneficial for the entire

crop community.

chemicals added to the soil by the grass) is at work in the

crop mixture.

These data raise other questions. For example, what

would happen in a crop mixture where the two species

involved had very similar nitrogen needs and procurement

abilities? Under conditions of limited nitrogen supply,

competition would probably result, and both species might

suffer, but eventually one would begin to dominate the

other. But another outcome is possible. The two different

species could have complementary ways of using nitrogen

when it is in limited supply; their timing of growth might

be different, or their root systems might occupy different

regions in the soil. They could thus avoid competition and

coexist in the same system.

COMPLEXITY OF INTERACTIONS

The ways in which the various populations of a crop

community influence the community as a whole through

their interferences may be complex and difficult to dis-

cern. An example will help illustrate this point.

Canopy development over time was studied in a grass

and clover mixture. The data from this study are shown

in Figure 15.2. When the interaction between grass and

clover is considered without any nitrogen being added, it

appears that competition for limited light under the canopy

of the crop mixture takes place. Shading by the clover

appears to inhibit the grass. We could conclude from these

data that due to its mutualism with nitrogen-fixing bacte-

ria, the clover is able to avoid nitrogen competition and

establish dominance. But the data obtained from adding

different amounts of nitrogen fertilizer to the mixture alter

the picture of community dynamics. The effect of adding

nitrogen is to shift the balance of species dominance; by

the last sample date the mixture at low nitrogen levels is

dominated by clover, but the mixture at high nitrogen

levels is dominated by grass. The advantage of one crop

over the other is altered by the availability of nitrogen,

with grass becoming more dominant as nitrogen supply

is increased. These data lead to somewhat different

conclusions; perhaps competition for light is the key

factor, or perhaps some complex interaction of light, nitro-

gen availability, and some other factor (e.g., allelopathic

C

OEXISTENCE

In complex natural communities, populations of ecologi-

cally similar organisms often share the same habitat without

significant apparent competitive interference, even though

their niches overlap to a considerable degree. Similarly, it

is often the case in natural communities that more than

one species shares the role of dominant species. It would

appear, then, that the principle of competitive exclusion,

which implies that two species with similar needs cannot

occupy the same niche or place in the environment, does

not fully apply in many communities.

The ability to “avoid” competition and instead coexist

in mixed communities leads to advantages for all involved

members of the community. Therefore, this ability may

well provide significant selective advantage in an evolu-

tionary sense. Although selection for competitive ability

has undoubtedly been very important in evolution, ecolo-

gists who study evolutionary biology now more widely

accept the idea that selection for coexistence may be more

the rule than the exception, especially in more mature

communities (Pianka, 2000).

Search WWH ::

Custom Search