Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

of islands of the world, discussing how animals and plants

reach islands that either have had a physical connection

to an adjacent mainland colonizing source or that have

never had such a link. The work of Van der Pijl (1972)

on the

Principles of Dispersal in Higher Plants

goes into

great detail on the incredible diversity of mechanisms that

aid seeds in moving from one place to another. These

mechanisms can move an organism only a short distance,

or great distances across amazing barriers of ocean or

desert. They can also get a weed seed to a new field.

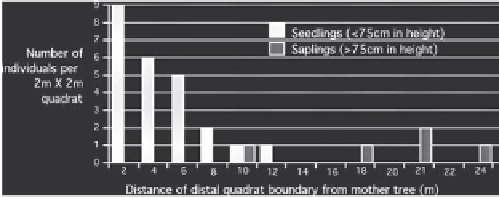

An important aspect of dispersal mechanisms is how

many of them seem to provide a selective advantage for

“getting away” from the source of reproduction. This is

illustrated by field studies done on the distribution of

seedlings around “mother trees” in the forests of Costa

Rica. As shown in Figure 13.2, most of the newly germi-

nated seeds and very young seedlings were concentrated

close to the tree, but the older saplings (with potential for

becoming adult, reproductive individuals) were found at

a greater distance. Some intraspecific mechanism (e.g.,

competition, and allelopathy) seems to eliminate seedlings

from near the tree, and does not function at a greater

distance. It is interesting to consider why there is advan-

tage in establishing at some distance from the parent,

especially in relation to resource availability, potential

competition, and susceptibility to predation or disease.

Plant seeds are incorporated into the soil soon after

they fall onto the soil surface, with the largest numbers

found in the upper layers of soil. The population of each

species of seed combines with others to form the

seed

bank

. In cropping systems, the analysis of the weed seed

bank can tell us a great deal about the prior history of

management of a site and the potential problems that

weeds may pose; this information can be important for

designing appropriate management.

Since most crop organisms are dependent on humans

for dispersal, their adaptations for dispersal have become

irrelevant for the most part. Indeed, most crop species have

lost the dispersal mechanisms they had as wild species.

Their seeds have become too large, the seeds have

lost appendages that once facilitated dispersal, or their

inflorescences no longer scatter seed. The loss of dispersal

adaptations is seen particularly in annual crops, whose

seed or grain is the portion of the crop that is harvested.

Establishment

There really is no bare area on the earth that propagules

of plants and animals cannot get to. The incredible diver-

sity of dispersal mechanisms mentioned above makes sure

of that. But once a propagule arrives at a new location, it

most certainly can have problems getting established.

Restricting our attention to plants, a dispersing seed can-

not determine where it will land; so it is the condition of

the site that determines if the propagule can establish.

Seeds fall into a very heterogeneous environment, and

only a fraction of the sites encountered will meet the needs

of the seed. Only those microsites that fulfil the needs of

the seed — the “safe sites” — can support germination

and establishment. The greater the number of a species'

seeds that land in safe sites, the greater the chance of that

species establishing a viable population in the new habitat.

The seedling stage is generally known to be the most

sensitive period in the life cycle of the plant, and is there-

fore a critical stage in the establishment of a new popu-

lation. This is true for crop species, weeds, and plants in

natural ecosystems. A dormant seed can tolerate very dif-

ficult environmental conditions, but once it germinates,

the newly emerged seedling must grow or die. Any one

of the many extremes of environmental conditions the

seedling might face can eliminate it, including drought,

frost, herbivory, and cultivation. Human intervention can

help ensure the successful and uniform establishment of

crop seedlings, but the variability of the environmental

complex still makes this the most sensitive phase for most

crop plant populations. Early juvenile stages of most ani-

mals show the same sensitivity to environmental stress.

Growth and Maturation

Once a seedling has successfully established, its main

“goal” is continued growth. The environment in which

seedlings are located, as well as the genetic potential the

seeds contain, combine to determine just how quickly they

will grow. In natural ecosystems, environmental factors

such as drought or competition for light generally limit

the growth process at some phase of the plants' develop-

ment. If these factors become too extreme, individuals in

the population will die.

Plants generally grow fastest, as measured by net bio-

mass accumulated over time, in the early stages of growth.

Their rate of growth slows as maturation begins — more

energy is allocated to maintenance and the production of

reproductive organs than to the production of new plant

tissue. Growth may also slow if the resources available

for each member of the population become limiting.

The time period from germination to maturity can

range from a matter of days for some annuals to several

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

Seedlings ( <75cm in height)

Saplings ( >75cm in height)

Number of

individuals per

2m × 2m

quadrat

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

21

22

24

Distance of distal quadrat boundary from mother tree (m)

FIGURE 13.2

Distribution of seedlings and saplings of

Gavilan

schizolobium

on a westerly strip transect away from

the mother tree, Rincon de Osa, Costa Rica.

Data from Ewert

and Gliessman, 1972.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search