Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

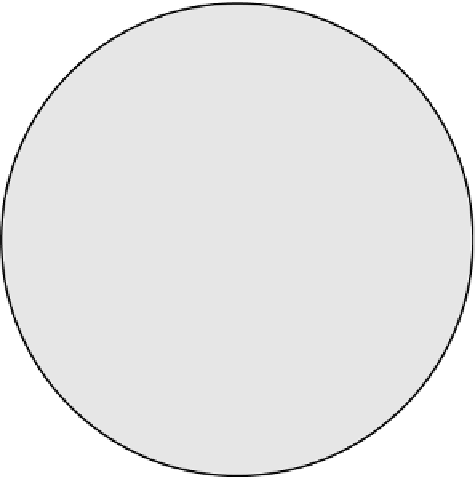

the “safe site.” Factors immediately surrounding the seed

are what influence the seed most directly. Factors around

the outside perimeter of the diagram are factors and vari-

ables that influence the effect, degree, or presence of the

direct factors.

Solar radiation

Relative

humidity

Temperature

Humans

Atmospheric

composition

Associated

animals

HETEROGENEITY OF THE ENVIRONMENT

Wind

The environment of any individual organism varies

not only in space but also in time. The intensity of each

factor in Figure 12.1 shows variation from place to place

through time, with an average for each factor setting the

parameters of the habitat within which each organism is

adapted. When variation in a factor exceeds the limits of

tolerance of an organism, the effects can be very damag-

ing. Farming systems that take this variation into account

are much more likely to have a positive outcome for the

farmer.

Crop

organism

Associated

plants

Rainfall,

irrigation

Soil

nutrients

Fire

Soil

Topography,

latitude

Parent

material

Gravity

FIGURE 12.1

Representation of the environmental complex.

The environment of an individual crop plant is made up of many

interacting factors. Although the environment's level of

complexity is high, most of the factors that make it up can be

managed. Recognizing factor interactions and the overall

complexity of the environment is the first step toward sustainable

management. (Adapted from

Billings, W. D. 1952.

Quarterly

Review of Biology

27: 251-265.)

S

PATIAL

H

ETEROGENEITY

The habitat in which an organism occurs is the space

characterized by particular combinations of factor inten-

sities that vary both horizontally and vertically. Even in a

field planted to a single variety of grain crop, for example,

each plant will encounter slightly different conditions

because of spatial variation in factors such as soil, mois-

ture, temperature, and nutrient levels. The amount of vari-

ation in these factors will depend upon the extent to which

the farmer tries to create uniformity in that field with

equipment, irrigation, fertilizers, or other inputs. Regard-

less of these attempts, however, there will be slight vari-

ation in topography, exposure, soil cover, and so on that

will create microenvironmental differences across the

space of the field. Very small variations in microhabitat,

in turn, can bring about shifts in crop response.

In a wet tropical lowland environment, for example,

where soils are poorly drained and rainfall is high, slight

topographic variation can make a big difference in soil

moisture and drainage. In such an area, the lower lying

areas of a field may be subject to much more waterlogging

than the rest of the field, and crop plants growing there

may experience arrested root development and poorer per-

formance, as illustrated in Figure 9.3. Some farmers in the

region of Tabasco, Mexico, where the photograph in

Figure 9.3 was taken, plant waterlogging-tolerant crops,

such as rice or local varieties of taro (

Colocasia

spp. or

Xanthosoma

spp.), in the lower lying areas of their farms

as a way of making a better match between crop require-

ments and field conditions. Finding ways to take advan-

tage of the spatial heterogeneity of conditions by adjusting

crop types and arrangements is often more ecologically

efficient than trying to enforce homogeneity or ignore

heterogeneity.

management, in contrast, begins with the farm system as

a whole and designs interventions according to how they

will impact the whole system, not just crop yield. Inter-

ventions may be intended to modify single factors, but the

potential impact on other factors is always considered

as well.

C

OMPLEXITY

OF

I

NTERACTION

The way in which a complex of factors interacts to impact

a plant can be illustrated by seed germination and the “safe

site” concept of Harper (1977). We know from ecophy-

siological studies that an individual seed germinates in

response to a precise set of conditions it encounters in its

immediate environment (Naylor, 1984). The locality at the

scale of the seed that provides these conditions has been

termed the

safe site

. A safe site provides the exact require-

ments of an individual seed for the breaking of dormancy,

and for the processes of germination to take place. In

addition, there must be freedom from hazards such as

diseases, predators, or toxic substances. The conditions of

the safe site must endure until the seedling becomes inde-

pendent of the original seed reserves. The requirements

of the seed during this time change, and so the limits of

what constitutes a safe site must also change.

Figure 12.2 describes some of the environmental fac-

tors that influence the germination of a seed and make up

Search WWH ::

Custom Search