Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

Male ratio

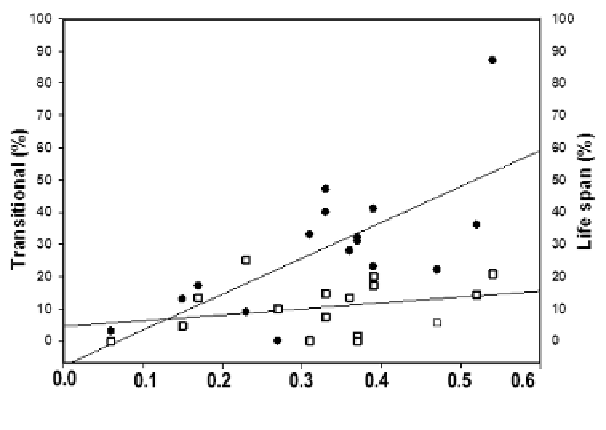

Fig. 42.

Relationships between male ratio and transitional load (□) carried during the life spawn

(●) of some protogynous hermaphrodites. (data are drawn from Table 20 of Pandian, 2010).

In formalizing the 'size advantage model', Warner (1975) has shown

that if age-specifi c reproductive output increases more rapidly with body

weight for one sex than the other and if the curves relating to fecundity

with body size/age cross each other, then in principle an age or body size,

at which an individual may reproductively profi t by switching gender.

Many scientists (e.g., Avise and Mank, 2009) have not recognized that

body size-fecundity relation can differ from that of age-fecundity, and

fi shes may also experience menopause stage. Whereas fecundity increases

with body size of fi sh, it does not during the period of terminal age (see

Pandian, 2010, Fig. 43). When a fi sh has attained > 70% of its maximum age,

it is approaching reproductively more or less inactive menopause stage at

its terminal life span . In different populations of the guppy

P. reticulata,

this period of terminal life span has been estimated to range between 12

and 15% of total life span (Reznick et al., 2006). The empirical estimation

predicts that sequential hermaphrodites change sex, when they reach 80%

of their body size (Allsop and West, 2003). When all the recent information

is taken together, it seems that the sequentials reach a body weight of 80%

of their maximum, corresponding to the completion of 80-85% of their life

span, when they produce negligible number of eggs (in relation to body

weight and time, Fig. 27, 31) or cease to produce eggs, the protogynous

hermaphrodites switch to males.