Biomedical Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

attempted from a donor animal of the same species without

a cross-match. In most cases, the risk of life-threatening

immunological reaction is minimal if it is the first time the

animal has received a transfusion even if the donor and

recipient are mismatched.

Once a need for transfusion has been established, the

goal should be to provide volume resuscitation via crys-

talloids and/or colloids and whole blood or pRBCs until the

hematocrit is 25 or greater (

Winberg, 2009

). Whole blood is

collected using aseptic technique into a collection syringe

that contains an anticoagulant. Most whole blood donor

collection reservoir kits used in veterinary medicine extract

too much volume and cannot be used directly for the most

commonly used species of nonhuman primates. If these

commercial systems are to be used, the anticoagulant must

be removed from the system and then added back at the

correct volume to match the collected blood volume.

Anticoagulants that may be used include acid-citrate-

dextrose (ACD) at a ratio of 1:9 with whole blood, heparin

at 10 units/ml whole blood, or 3.8% citrate at a ratio of 1:9

if transfusion will immediately follow collection (

Brainard,

2009

; California National Primate Research Center

(CaNPRC), 2009). For healthy donors who have not had

blood collected within the previous 30 days, 10 ml whole

blood/kg body weight can be collected safely.

Blood is administered to the recipient aseptically via

a standard blood filter line so as to prevent administration of

clots (

Figure 15.3

). Filters are also available that can be

attached to intravenous administration lines. Blood should

be administered at a rate of 1 ml/kg for the first 15 minutes

and at a maximum rate of 22 ml/kg/h thereafter (

Brainard,

2009

). Temperature, pulse, and respiratory rate are assessed

prior to administration and at regular and frequent intervals

during administration to detect adverse reactions. Adverse

reactions are immune-mediated and may include urticaria,

and pruritus if mild, or collapse, tremors, tachycardia, and

death if severe (

Brainard, 2009

). In addition, animals

should be monitored for several hours post transfusion for

clinical signs of acute respiratory distress syndrome

(ARDS) and supported with oxygen if respiratory signs

develop. Other supportive therapy (antihistamine, cortico-

steroids, intravenous fluids) should be instituted as neces-

sary if adverse reactions occur.

Cardiopulmonary Cerebral Resuscitation

Cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA) is characterized by the

sudden cessation of spontaneous and effective circulation

and ventilation. The diagnosis of CPA is based on the

absence of effective ventilation, severe cyanosis, absence

of a palpable pulse or apex heartbeat, absence of heart

sounds, and ECG evidence of asystole or other non-

perfusing rhythm such as pulseless electrical activity

(PEA; formerly referred to as electromechanical dissoci-

ation), pulseless ventricular tachycardia, or ventricular

fibrillation. If the primary disease state causing cardio-

pulmonary arrest is reversible, prompt assessment and

intervention focused on maintaining circulation may save

the animal's life. In recent years, it has been acknowl-

edged that maintenance of cerebral circulation is as

important as cardiac perfusion (

Ford and Mazzaferro,

2005; Plunkett and McMichael, 2008; Wells, 2008

).

Cardiopulmonary cerebral resuscitation (CPCR) provides

artificial ventilation and circulation until advanced life

support can be provided or return of spontaneous circu-

lation (ROSC) occurs. Animals experiencing cardiopul-

monary arrest have historically had a poor prognosis, even

with appropriate intervention, and this may be the result of

underlying disease processes that exist. In species of

nonhuman primates with cardiomyopathy including Aotus

and macaque species, the underlying disease process

results in poor response to resuscitation efforts and a poor

prognosis. In veterinary medicine, even with aggressive

treatment and management, the overall success of CPCR

is less than 5% in critically ill or traumatized patients and

20% to 30% in anesthetized patients (

Ford and Mazza-

ferro, 2005

). Diagnosis of the primary disease state will

help determine if CPCR is warranted. Considerations for

resuscitation of nonhuman primates should be consistent

with the approved experimental endpoints if animals are

assigned to research protocols.

In 2010 the American Heart Association (AHA) pub-

lished new guidelines for CPCR in humans (

Neumar et al.,

2010

). Highlights of the new guidelines include a greater

emphasis on chest compressions, avoidance of excessive

ventilation rates, and immediate resumption of compres-

sions after a single defibrillation. Many of the recommen-

dations are based on research in small animals (canine and

feline) and are pertinent to veterinary patients. Much of the

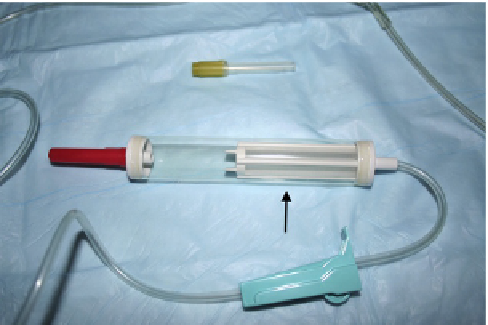

FIGURE 15.3

Whole blood administration set for transfusion. The

reservoir (arrow) contains a filter to remove blot clots as whole blood is

administered. Whole blood should never be administered using standard

intravenous fluid drip sets without filters.