Biomedical Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

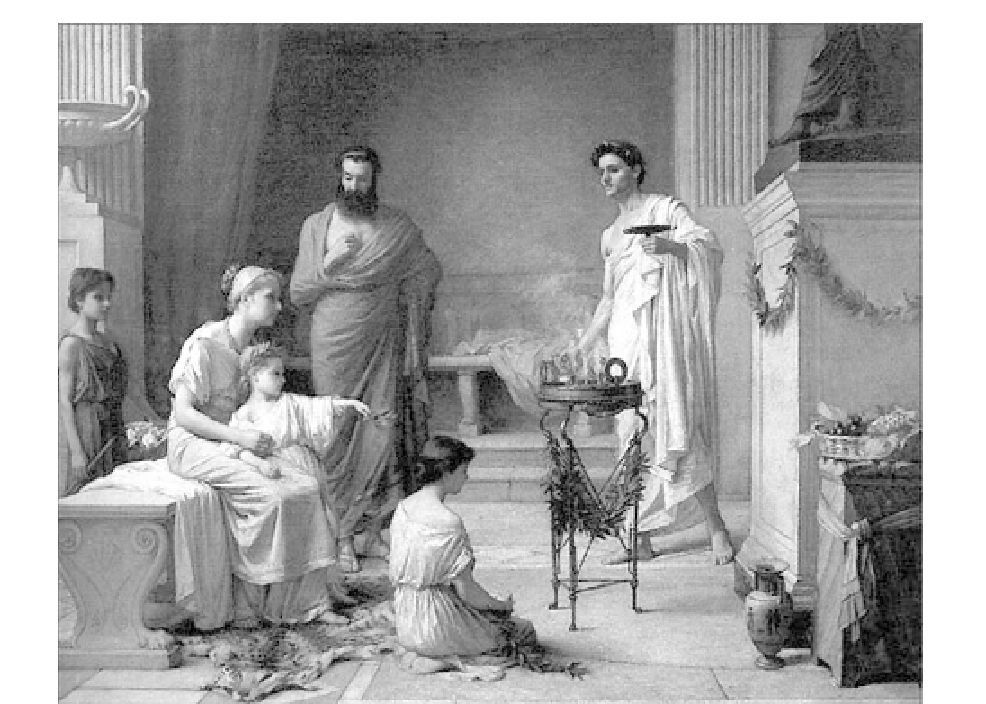

FIGURE 1.1

A sick child brought to the Temple of Aesculapius.

Courtesy of http://www.nouveaunet.com/images/

art/84.jpg.

the night, “healers” visited their patients, administering medical advice to clients who were

awake or interpreting dreams of those who had slept. In this way, patients became convinced

that they would be cured by following the prescribed regimen of diet, drugs, or bloodletting.

On the other hand, if they remained ill, it would be attributed to their lack of faith. With

this approach, patients, not treatments, were at fault if they did not get well. This early use

of the power of suggestion was effective then and is still important in medical treatment

today. The notion of “healthy mind, healthy body” is still in vogue today.

One of the most celebrated of these “healing” temples was on the island of Cos, the birth-

place of Hippocrates, who as a youth became acquainted with the curative arts through his

father, also a physician. Hippocrates was not so much an innovative physician as a collector

of all the remedies and techniques that existed up to that time. Since he viewed the physi-

cian as a scientist instead of a priest, Hippocrates also injected an essential ingredient into

medicine: its scientific spirit. For him, diagnostic observation and clinical treatment began

to replace superstition. Instead of blaming disease on the gods, Hippocrates taught that

disease was a natural process, one that developed in logical steps, and that symptoms were

reactions of the body to disease. The body itself, he emphasized, possessed its own means

of recovery, and the function of the physician was to aid these natural forces. Hippocrates

treated each patient as an original case to be studied and documented. His shrewd