Biomedical Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

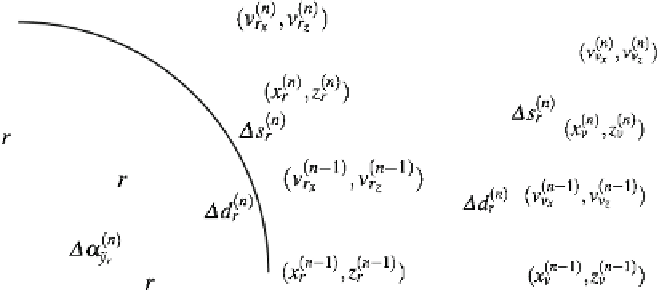

(a)

physical movement

(b)

virtual motion

Fig. 10.3

Illustration of two-dimensional mappings in the

xz

-plane from (

a

) tracking coordinates

to (

b

) virtual coordinates for an applied curvature gain

g

C

/

r

with radius

r

∈ R

+

=

1

virtual

camera

coordinates

(b)

virtual motion

(a)

physical movement

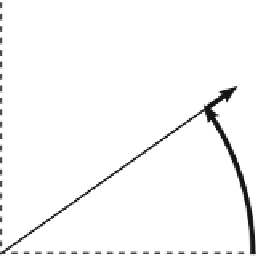

Fig. 10.4

Illustration of (

a

) path redirection with curvature gains in the physical workspace, for

(

b

) a predicted virtual straight path

v

(

n

)

v

(

n

)

v

(

n

)

v

(

n

)

2

with

(

,

)

∈ R

(

,

)

=

in Fig.

10.3

a, as well as

1 in the virtual

workspace shown in Fig.

10.3

b. Other implementations may use arbitrarily placed

curvatures in the physical workspace, e.g., based on real and virtual path planning and

transformations [

20

,

26

,

34

]. Figure

10.4

shows an example of a predicted straight

motion in the VE being mapped to a circular path in the physical workspace.

It is important to note that curvature transformations are based on the assumption

that the user will adapt to induced virtual rotations by changing the walking direction

in the physical workspace. In particular, if the manipulations are overt, the user has

to consciously follow the induced virtual rotations. If the user does not adapt to an

induced rotation in the virtual environment, e.g., if the user is walking with eyes

v

x

v

z

v

x

v

z