Biomedical Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

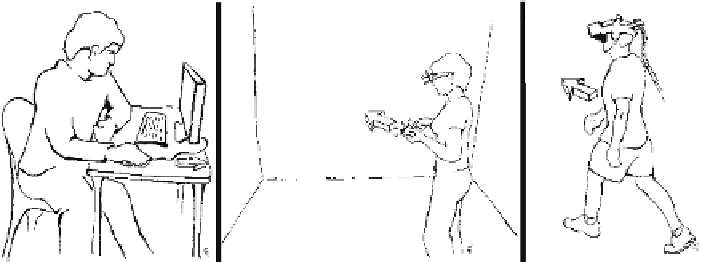

(b)

(c)

(a)

Fig. 1.1 a

A user of a typical desktop VE system, which offers comparatively impoverished sen-

sory information to users. The primary navigation interface in this case is the mouse and keyboard.

Somatosensory, ideothetic, and inertial sensory information about virtual movements are not avail-

able, as the user's body is stationary. Visual field-of-view is also typically limited in desktop displays.

b

A user in a typical CAVE system, which visually surrounds her. The user is free to turn and look

about and she can move freely over a small area. The primary navigation interface in this case

is a wand-type device. CAVEs offer relatively wide and physically-accurate visual field-of-view

and typically feature surround-sound audio, but sacrifice veridical somatosensory, idiothetic, and

inertial sensory feedback over large ranges.

c

A user in a typical HMD system. The primary navi-

gation interface is the user, who can walk and turn naturally. Range of navigation is limited in some

systems by the cable length or, if the rendering computer is worn, the size of the tracking area.

Visual field-of-view is typically limited in HMDs

1.4.2.1 Desktop Virtual Environments

Classic Desktop Systems

In a traditional desktop VE (Fig.

1.1

a), a stationary user is seated in front of a display

and uses a set of arbitrary controls to navigate through a virtual space (e.g., press

“w” to move forward). This can include simulations that are presented on desktop

computers, laptops, or on a television using a gaming console. While such simula-

tions can contain accurate positional audio and optic flow that inform users about

the simulated movement of the depicted viewpoint, the simulation presents nearly all

other spatial senses with information that does not match. The user's idiothetic senses

will report—quite accurately—that she is sitting still even though the images on the

screen simulate her movement. Likewise, traditional efferent information about the

user's intended movements (e.g., “walk 2m forward”) are replaced with information

about intended button presses and joystick movements that map to unknown units of

translation and rotation. This leaves the user not only in a state of sensory conflict,

but also removes sensory-motor feedback that can be useful for accurate path inte-

gration [

16

,

76

]. Above, we noted that idiothetic information seems to be particularly

important for tracking rotational changes (e.g., [

55

]), and as such, it can logically be

expected that users of desktop VE will have relative difficulty with updating their

current heading and integrating multiple legs of a journey to keep track of their ori-

entation within a virtual world. This may lead to users becoming lost and disoriented