Biomedical Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

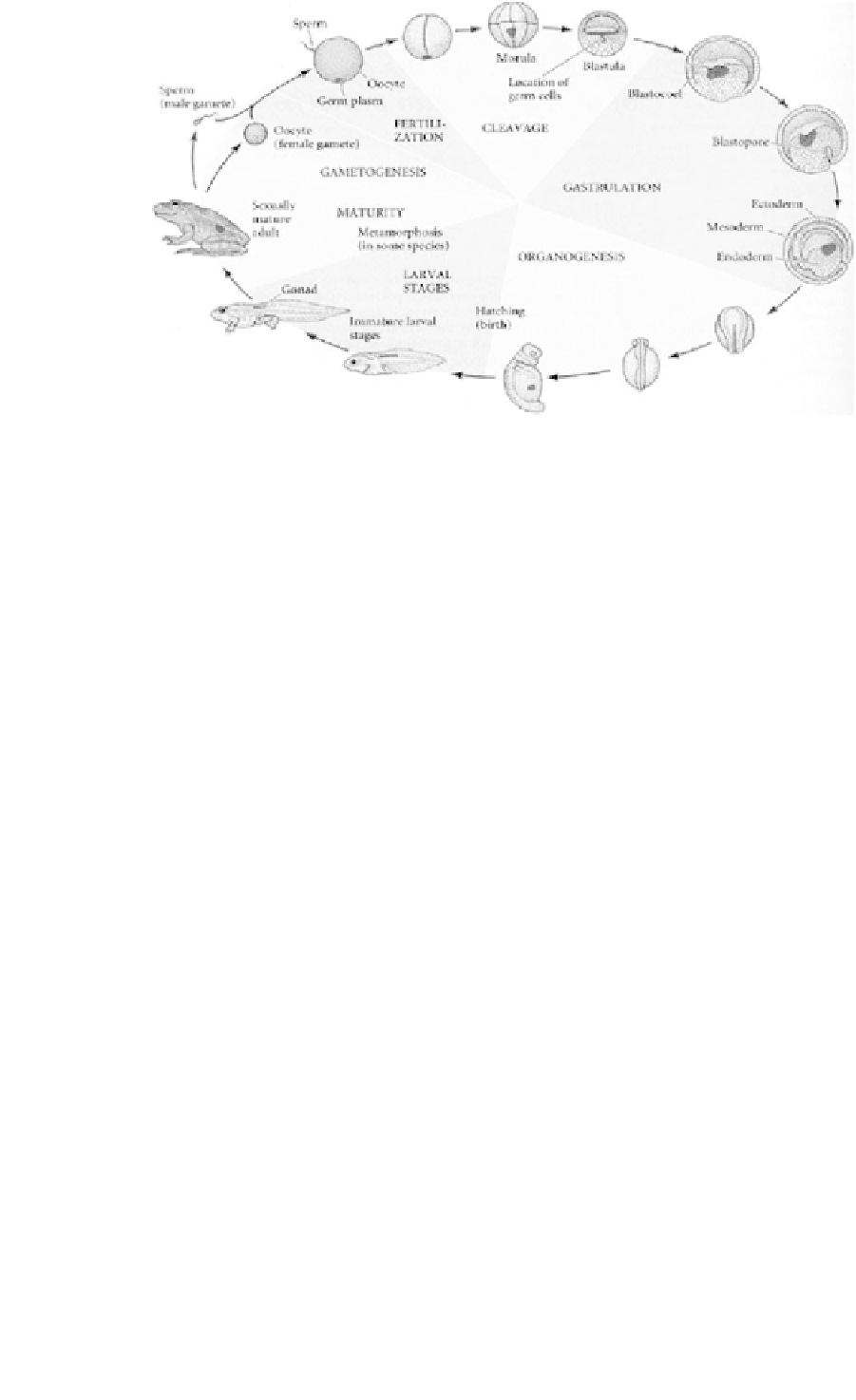

Figure 8.2-2 Stages of stem cell development in a frog. Note the continuity of germplasm.

Adapted from: The President's Council for Bioethics, 2004, Monitoring Stem Cell Research, Appendix A, Washington, DC.

(i.e., multipotent) cells have been isolated from a variety

of tissues. These stem cell populations can be differen-

tiated

in vitro

into various cell types, and are currently

being extensively and intensively investigated for po-

tential applications in regenerative medicine. Many sci-

entists believe that embryonic and adult stem cells can

lead to treatments for many human maladies. However,

much of this is conjecture at this point.

The Chairman of the President's Council on Bioethics

succinctly characterized the raging stem cell debate in

a letter to the President:

the value of the individual, fertilized ova, destroying and

discarding many in the process.

In a recent undergraduate seminar at Duke, students

shared why IVF seems to ''get a pass'' morally, at least in

comparison to the scrutiny given to stem cell and cloning

research, even though all these are beginning of life

(BOL) issues. One student pointed out that IVF is not

new. Others noted that the technologies are more

mainstream and understandable by the public. One stu-

dent suggested the fact that many people know people

who were conceived via IVF, so the mystique is gone. In

the course of the discussion, it became obvious that most

of the students do not even think about the morality of

IVF. It simply exists as an alternative means of re-

production. And, the IVF industry is considered rather

positively. The discarded embryos are just considered by

many to be a byproduct of the process that allows people

who could not ordinarily do so to have children. Thus,

few seem to question the morality of IVF, so the

discarding of embryos is not often seen as an immoral

act of the fertility clinics. Further, those who oppose the

use of embryos that would otherwise be destroyed are

seen as ''wasteful'' and ''myopic,'' or even as Luddites

who stand in the way of progress and betterment of

humankind.

As the President's Council on Bioethics puts it: ''All

extractions of stem cells from human embryos, cloned or

not, involve the destruction of these embryos.''

10

A rather

common paradox is that research may either exacerbate

or ameliorate ethical issues. For example, if emerging re-

search supports the contention that embryonic stem cells

are essential to provide the treatment and cures of in-

tractable diseases, many scientists and ethicists will push

the ''greater good,'' utilitarian viewpoint, while others will

While they may well in the future prove to be of

considerable scientific and therapeutic value, new

human embryonic stem cell lines cannot at present be

obtained without destroying human embryos. As

a consequence, the worthy goals of increasing scientific

knowledge and developing therapies for grave human

illnesses come into conflict with the strongly held belief

of many Americans that human life, from its earliest

stages, deserves our protection and respect.

9

The diametric opposition lies between those who see

embryos as living human beings entitled to protection and

those who consider them merely as ''potential'' humans

that may be used as researchers see fit in an effort to

advance the state of knowledge. This use includes the

destruction (killing) of embryos to harvest stem cells.

One of the major ethical issues of stem cell research

revolves around the first stage, especially the means of

harvesting the embryonic stem cells by IVF. In particular,

the argument contends that since fertilization has oc-

curred, we are actually conducting research on a living

human being. And, the IVF process itself is cavalier about