Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

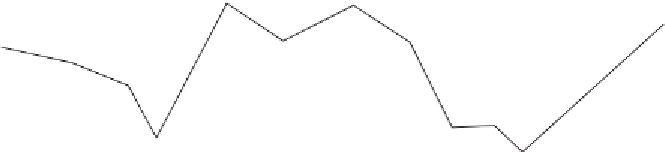

Figure 2.5

Population growth rate of China's western provinces and regions, 1949-2000.

Data from UNESCAP (2004) and China Map Publishers (1984). Data for Tibet

supplemented from Grunfeld (1996). Interpolations for years with data for only

some provinces interpolated by author. Dashed line with solid circles represents

overall mean growth rates for China during the same time periods.

1.08

1.06

1.04

1.02

1.00

0.98

1949

1959

1969

1979

1989

1999

Gansu

Inner Mongolia

Ningxi a

Qingha i

Tibet

Xinjiang

China

memory is also frequently voiced by pastoralists, and is usually given as among the rea-

sons that forage seems less plentiful than in earlier times. Local informants also talk of

natural springs, formerly reliable, that have dried up in recent decades. Data abound on

rivers that no longer flow as they once did, and on retreating glaciers, all contributing to

a sense of gloom and the notion that perhaps western China has just gotten particularly

unlucky of late: an already dry place just happens to be getting even drier.

The veracity of these claims is relevant to the examination of wildlife conservation in

western China. If there really has been a general, long-term drying trend, then carrying

capacity of the land for both livestock and wildlife should have declined. Thus, conflicts

that might exist in any case would have been exacerbated regardless of how people man-

aged themselves, their animals, or the grasslands their animals depend on. Even if such

a general drying trend were part of the global climate change arising from the increasing

accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere—and thus qualified in some sense as

anthropogenic as opposed to simply being part of some larger atmospheric fluctuation—it

would simply exist as an unfortunate fact that both people and wildlife in China's west

must cope with. The best possible management practices or most eco-friendly attitudes

would be of little use against such a global phenomenon.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search