Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

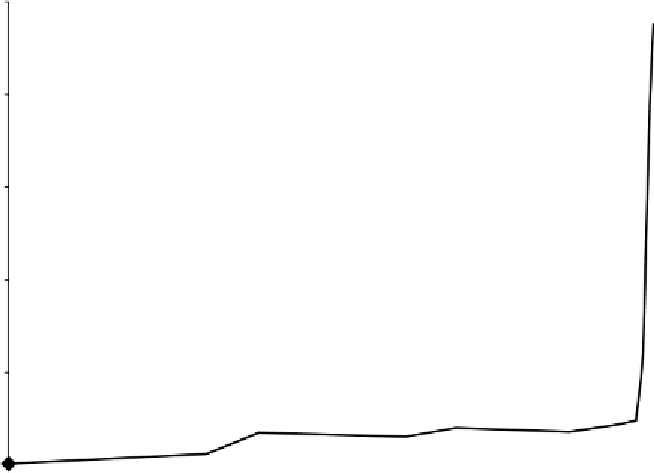

Figure 7.2

Estimated human population of Inner Mongolia, from ancient times to present.

Historical data from Wen (1995); 2000 data from UNESCAP (2004).

25

2000

20

1982

15

10

5

1949

1937

0

1912

1575

742 AD

265 BCE

1267 BCE

stock, unwilling—if physically quite able—to graze among or within domestic animals,

and no doubt was displaced by dogs and other domestic animals that usually came with

people. Of course, Przewalski's gazelle were hunted locally for meat, particularly during

the Great Leap Forward, but there is nothing in what we know of their population dy-

namics which suggests that they should be any less able to sustain hunting pressure than

the other gazelle species. Rather, if subsistence hunting was disproportionately focused

on the Przewalski's gazelle, it was probably because they were closer by. It appears that

hunting and direct forage competition played subsidiary roles to appropriation of land by

humans with their agriculture and livestock in the demise of Przewalski's gazelle from

its former low-elevation habitats. In the case of the closely related and declining (but

still very much more abundant) Mongolian gazelle, we know that wild populations have

done well where people have remained sparse, but declined where human population

density has increased.

33

Until roughly the mid-1950s, the area around Qinghai Lake probably provided quite

a suitable place for the species to make a stand. Situated west of Sun-Moon (

riyue

) Pass,

which has traditionally been seen as a cultural border between China and Tibet, it was

populated primarily by Tibetan and Mongol pastoralists living a subsistence lifestyle.

The Xining Valley had been occupied by Han Chinese in good numbers since at least the

Han Dynasty, and we know that deforestation of the Huang He Valley leading up toward

Qinghai Lake had become severe by the early Qing Dynasty.

34

Tibetologist Graham Clarke

Search WWH ::

Custom Search