Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

Within these terranes the oldest rocks in the state are

to be found.

Although major events have been sketched out,

details of the geologic history are still only poorly

known. Geologists are now aware of the exotic nature

of most of the older rocks here, which have been

mapped and described as well as dated with fossils and

radioactive decay techniques. What remains is to

determine where each of the blocks or terranes origi-

nated as well as how and when they were transported

and accreted to North America.

Metamorphism, intrusion, and volcanic activity

annealed these exotic blocks to North America where

they became the foundation of northeast Oregon.

These remnants of the earth's crust in the Blue Moun-

tains offer an opportunity to study in detail a "collision

boundary", the point where multiple large-scale blocks

or tectonic plates have collided and merged with each

other. Here a natural outdoor laboratory is available to

view the wreckage of ancient islands that were cast up

on Oregon's prehistoric shores.

Following the accretion of the major exotic

terranes here, a vast shallow seaway of late Mesozoic

or Cretaceous age covered most of the state depositing

thousands of feet of mud, silt, and sand. This oceanic

environment of warm quiet embayments and submarine

fans was populated by ammonites and other molluscs

as well as by marine reptiles, while tropical forests of

giant tree ferns grew along the shore.

With uplift and gentle folding of the crust, the

shoreline, which ran northward through central Ore-

gon, retreated westward beyond the present day Cas-

cades, and a long interval of volcanism ensued. Thick

lavas intermittently oozed from fissues and vents

throughout the region during the Eocene and Oligo-

cene. Volcanic activity was interspersed with periods of

sedimentation and erosion when local basins or depres-

sions in the lava were filled with sediments deposited

there by streams. Reptiles, mammals, fish and plants

living in the tropical climate of this time died and were

buried in the volcanic sediments. Originating from

fissures in the Blue Mountains flow after flow of

Miocene lavas eventually covered almost a quarter of

the state. Areas of central and northeast Oregon were

a wasteland of dark basalt up to a mile thick. As the

lavas cooled and shrank, long vertical columns formed

within the layers. Today the harder basalts cap and

preserve many of the colorful rock displays.

Widespread glaciation in the Wallowas during

the Pleistocene gave the region its final unique appear-

ance. Beginning about 2 million years ago, the climate

rapidly grew colder with the advance of a continental

ice sheet southward as far as northern Washington,

Montana, and Idaho. Although the Wallowas weren't

entirely covered by ice, glaciers built up in valleys

formerly occupied by streams. At the height of the Ice

Ages, nine major glaciers spread through the moun-

tains, only to melt and retreat with warmer tempera-

tures.

Geology

Only in the past two decades has it become

apparent that the Blue Mountains province is actually

a number of smaller pieces of terranes which originated

in an ocean environment to the west. The word,

terrane, implies a suite of transported similar rocks

that are separated from adjacent rocks by faults. Seas

covered all of Oregon as far back as Triassic time, 200

million years ago, when these exotic blocks or terranes,

traversing the Pacific Ocean basin, began to collide

with the North American West Coast. As each of these

island blocks arrived, they successively docked against

the ancient North American craton, producing layered

bands of exotic terranes. The craton itself represents

the North American core or foundation of rocks native

to this continent.

Scattered along the North American West

Coast, these terranes are much more complex than

previously thought. New evidence suggests that after

collision movement of terranes by faulting was predom-

inantly southward up to late Triassic time, then north-

ward during the early and middle Jurassic, southward

in the late Jurassic and early Cretaceous, and then

finally northward from the late Cretaceous onward.

With such a complexity of movements, it is little

wonder that West Coast rocks look like a well-shuffled

deck of cards.

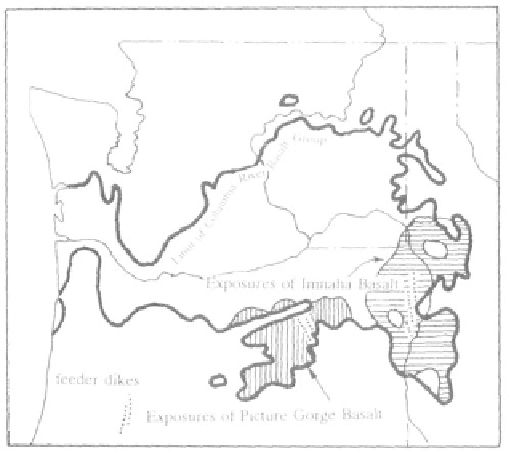

Distribution of Miocene Columbia River Group lava

flows in the Blue Mountains (after Anderson, et al.,

1987)