Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

Prior to each flood, an ice lobe from northern

Idaho stretched southwest to dam up the Clark Fork

River that flows northward to join the Columbia across

the Canadian border. Old shorelines visible today high

above the city of Missoula, Montana, are evidence that

the ice dam backed up a vast lake covering a large area

of western Montana. As the ice dam was breached,

water, ice, and sedimentary debris poured out at a rate

exceeding 9 cubic miles per hour for 40 hours. Flushing

through the Idaho panhandle and scouring the area

now known as the channeled scablands of southeast

Washington, the lake drained in about 10 days.

After crossing eastern Washington, the water

collected briefly at the narrows of Wallula Gap on the

Oregon border where blockage produced the 1,000 foot

deep Lake Lewis. Ponding up a second time at The

Dalles to create Lake Condon, the rushing water

stripped off gravels and picked up debris, steepening

the walls of the Columbia gorge. Near Rainier the river

channel was again constricted causing flood waters to

back up all the way into the Willamette Valley. At

Crown Point flood waters spilled south into the Sandy

River drainage and across the lowland north of Van-

couver taking over the Lacamas Creek channel. Most

of the water exited through the gorge to the ocean, but

as much as a third spread over the Portland region to

depths of 400 feet. Only the tops of Rocky Butte, Mt.

Tabor, Kelly Butte, and Mt. Scott would have been

visible above the floodwaters. Surging up the ancestral

Tualatin River, the waters covered the present day site

of Lake Oswego to depths over 200 feet, while Beaver-

ton, Hillsboro, and Forest Grove would have been

under 100 feet of water.

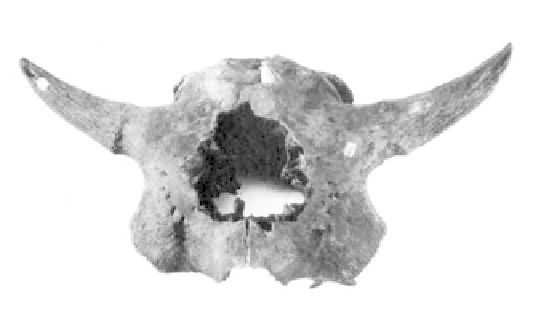

Skulls and skeletal elements of Ice Age bison up to

8 feet high at the shoulder are common in

Willamette Valley swamp deposits (specimen from

the Thomas Condon Collection, Univ. of Oregon).

canyon and tributary streams high in the upper water-

shed. The amount of water in a single flood, estimated

at up to 400 cubic miles, is more than the annual flow

of all the rivers in the world. The natural reservoir of

Lake Missoula filled and emptied repeatedly at regular

intervals suggesting that natural processes were regulat-

ing the timing of the floods. Once the lake had filled to

a certain level, it may have floated the ice lobe or

glacial plug that jammed the neck of the valley which,

in turn, released enough water to allow the flooding

process to begin.

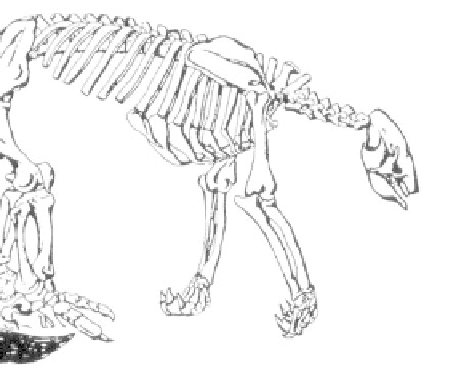

Swampy lowlands in the Willamette Valley yield the

bones of the enormous Ice Age ground sloth.