Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

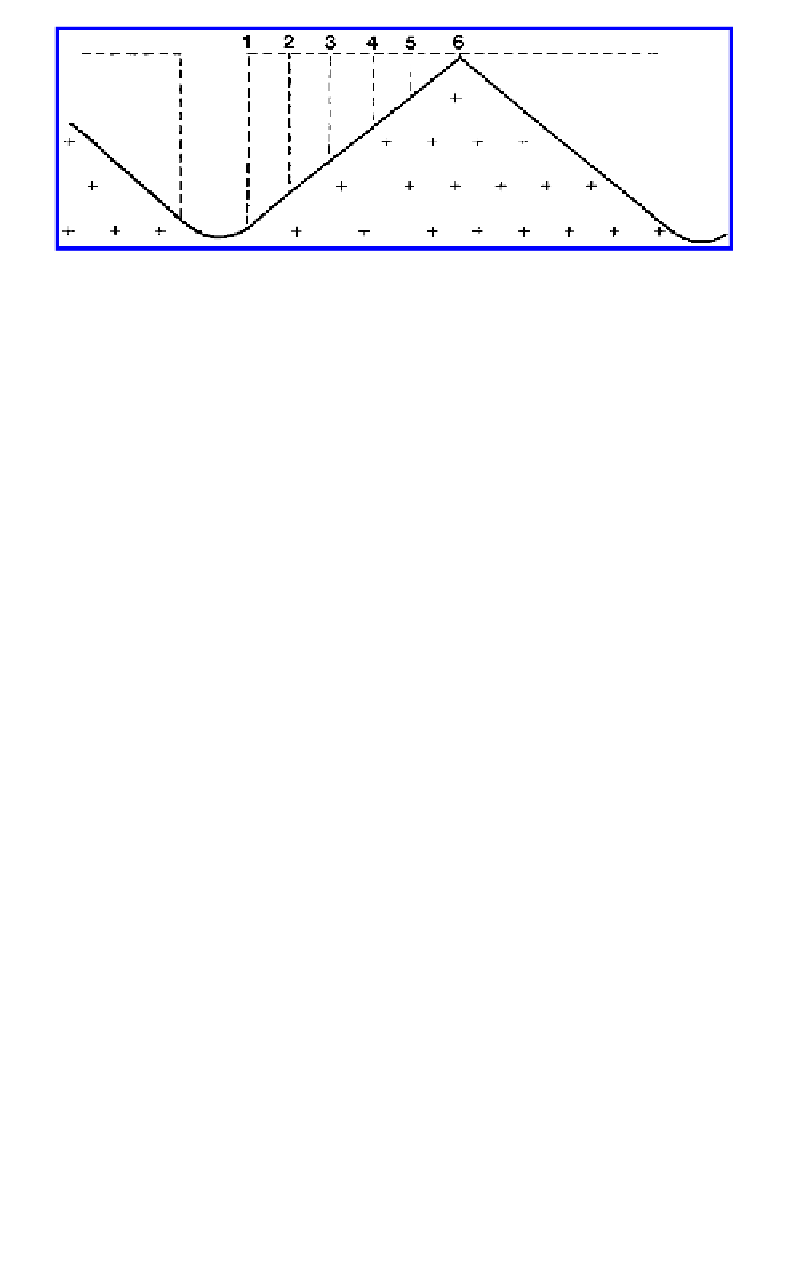

Figure 7.21.

Suggested mode of development of all slopes topography.

7.4

DISCUSSION

Bornhardts, nubbins and castle koppies are genetically related forms, the two last-named

being derived from the marginal subsurface weathering of domed forms. Nubbins and castle

koppies are the reduced remnants of bornhardts. Elements of the two forms are developed in the

same hill at some sites. Thus, in the southern face of Blackingstone Rock, on eastern Dartmoor,

southwestern England, huge quadrangular blocks are exposed, and the form is castellated, but

the northern side is dominated by massive convex-upward slabs of rock that give a domical

shape to the hill (Simmons, 1964 and see Fig. 2.12). According to Holmes (1918), Mt Kobe, in

Mozambique, also displays contrasted morphology on opposed aspects, and some of the residu-

als at the Devil's Marbles, Northern Territory, embrace elements of nubbins and koppies (cf. Figs

7.7b

and 7.9).

The basic form, the bornhardt, is a structural feature developed on masses that are compact by

virtue of their being in stress. They are characterised by, and owe their domical shape to, the devel-

opment of sheet structure as a result of shortening. Nubbins and castle koppies, on the other hand,

though strongly influenced by structure and also found in multicycle landscapes, are in some

measure morphogenetic features. Nubbins are best developed in humid, tropical areas as a result

of the superficial disintegration of the outer shells (sheet structure). Castle koppies, on the other

hand, are due to lateral or marginal weathering, also in the subsurface, and under various climatic

conditions (humid, tropical, arid or semi-arid, arctic or subarctic).

Weathering eventually reduces both nubbins and koppies, though the latter especially are very

durable. What remain are small domes which are frequently scarcely more than low, convex-

upward platforms with a scatter of blocks and boulders. They are nevertheless genetically related

to bornhardts. The dome structure is the starting point of an evolutionary sequence that can follow

varied paths. All three prominent inselberg forms are initiated in the subsurface.

REFERENCES

Bateman, P.C. and Wahrhaftig, C. 1966. Geology of the Sierra Nevada. In Bailey E.H. (Ed.), Geology of

Northern California. California Division of Mines and Geology Bulletin 190. pp. 107-172.

Caillère, S. and Henin, S. 1950. Etude de quelques altérations de la phlogopite à Madagascar.

Comptes

Rendues des Séances. Academie des Sciences de Paris

230: 1383-1384.

Demek, J. 1964. Castle koppies and tors in the Bohemian Highland (Czeckoslovakia).

Biulytyn Peryglacjalny

14: 195-216.

Godard, A. 1977. Pays et Paysages du Granite. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris.

Handley, J.R.F. 1952. The geomorphology of the Nzega area of Tanganyka with special reference to the for-

mation of granite tors. C.R. Congr. géol. International (Algiers). 21: 201-210.

Holmes, A. 1918. The Pre-Cambrian and associated rocks of the District of Mozambique.

Quarterly Journal

of the Geological Society of London

74: 31-97.

Huber, N.K. 1987. The geologic story of Yosemite National Park. United States Geological Survey Bulletin 1595.

Hume, W.F. 1925. The Geology of Egypt. Volume I. Government Printer, Cairo.