Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

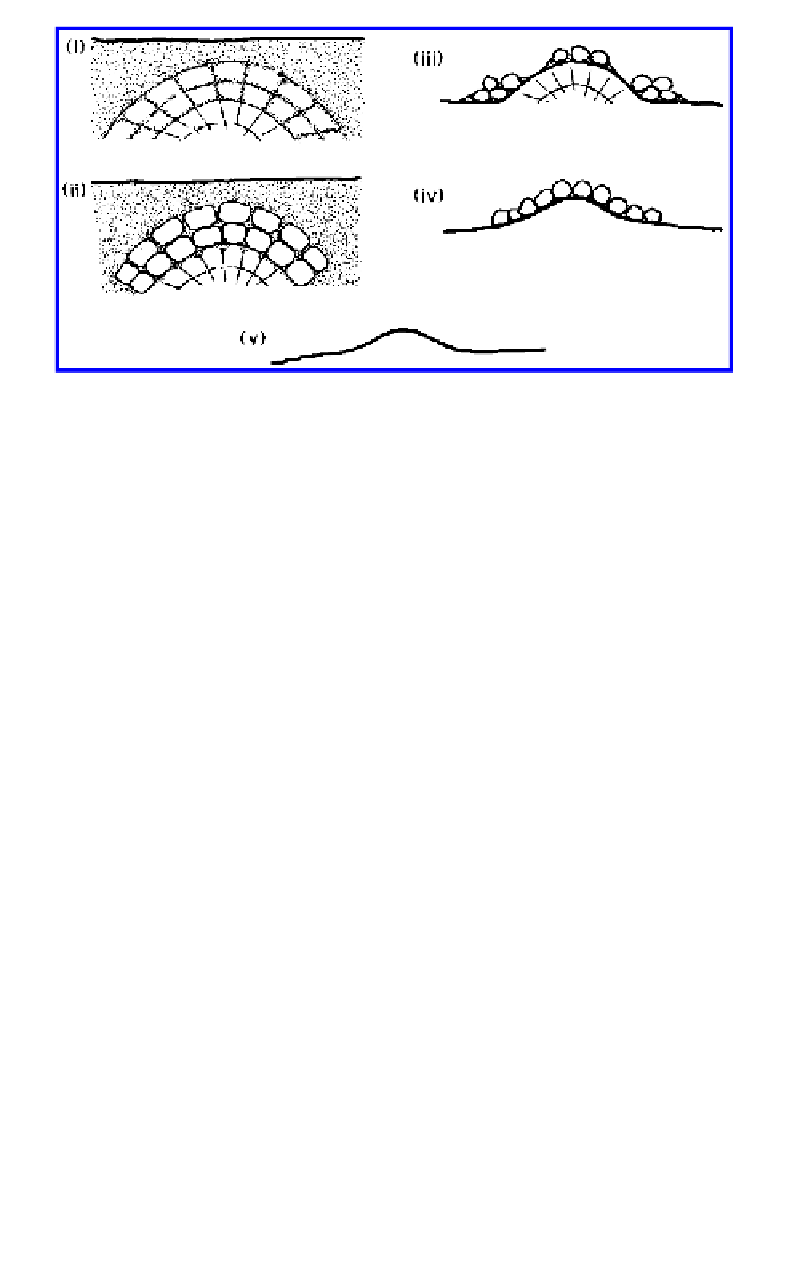

Figure 7.4.

Suggested development of nubbins.

which have been broken down to blocks and boulders through the exploitation of fractures dis-

posed normal to the domical surface and which may be related to tensional stresses in the crests of

antiforms (Ritchot, 1975).

There is considerable evidence that nubbins are associated with palaeosurfaces. The flattish

crests of nubbins in northwest Queenland, and near Alice Springs, Northern Territory, are readily

correlated with Late Tertiary palaeosurfaces of which they are thought to be part, possibly in etch

form, and below which deep differential compartment weathering took place under warm, humid

conditions. Handley (1952) has shown that what he called the tors (which are in reality nubbins)

of Tanganyika evolved beneath the African land surface of Early Cainozoic age. Those of the west-

ern Pilbara developed beneath either the Cretaceous Hamersley Surface, or the lower Eocene surface

on which the Robe River pisolite was deposited.

Thus, it is suggested that most nubbins have their origin in the subsurface and evolve par-

ticularly well in warm, humid climates, where weathering is sufficiently aggressive to cause the

blocky disintegration of the outer shell or shells of the convex-upward masses of still fresh rock

(Fig. 7.4). After the lowering of the plains and the exposure of the residuals, the continued break-

down of the blocks and boulders, and particularly the evacuation of the interstitial grus, causes them

to become disarranged as they tumble downslope under gravity. In this way, parts of the inner

dome are revealed.

7.1.2

. Castle koppies

Castle koppies are comparatively small, steep-sided castellated residuals (Figs 1.2d and

7.5)

.

They

stand in isolation, and Godard (1977) perceptively refers to castle koppies as inselbergs de poche,

indicating that the castellated forms are small compared with bornhardts. In any given area they

are lower and really less extensive than their domical counterparts. Orthogonal fractures dominate

koppies, and like bornhardts, some display evidence, in the form of zones of flares well above the

present plain level, of phased development (

Fig. 7.6)

.

Domed and castellated inselbergs developed in similar rock types coexist in the Harare-Mrewa-

Marandellas area of Zimbabwe and elsewhere. Again, at many sites castellated forms rest on

large-radius domes (

Fig. 7.7)

formed on identical bedrock. The angular morphology of castle kop-

pies undoubtedly reflects either widely spaced orthogonal fractures or a well-developed vertical

or near-vertical foliation. Thus, on Dartmoor, southwestern England (Simmons, 1964; Worth, 1953;

Waters, 1964) the Massif Central of France, the Bohemian Massif in the Czech Republic (Demek,

1964), the Karkonosze Mountains of southern Poland (Jahn, 1962), the Sierra de Gredos, central

Spain, the Traba Mountains (Costa da Morte, Galicia), the Pit

~

es dos Junhas in the Sierra de Xurès