Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

The hazards of natural ice islands (tabular icebergs) in

the waters of the Arctic Ocean, the Beaufort Sea, and the

Northwest Passage were assessed extensively during the

late‐1980s to assist in the safe operation of ships and off-

shore structures (particularly offshore drilling platforms).

Research activities had focused on ice island numbers,

morphology, and remote sensing [

Jeffries et al.

, 1988;

Jeffries and Sackinger

, 1989], dynamics, motion, and

recurrence intervals [

Lu

, 1988], physical‐structural char-

acteristics and stratigraphy [

Jeffries et al.

, 1988], strength‐

related properties of shelf ice [

Frederking and Sinha

, 1987;

Frederking et al.

, 1988;

Jeffries and Sackinger

, 1990, 2012],

and medium‐scale, macroscale in situ strength and labora-

tory strengths of MY ridge ice [

Gagnon and Sinha

, 1991;

Meaney et al.

, 1992]

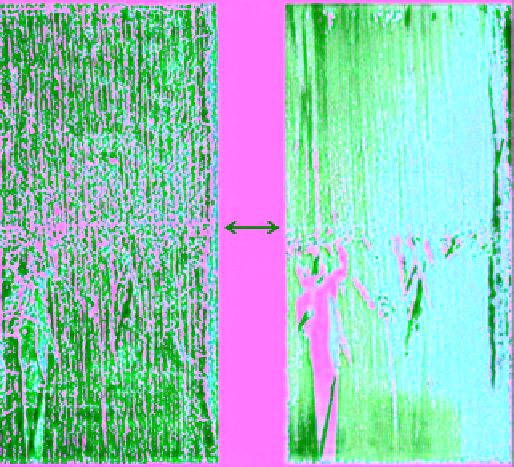

(a)

(b)

3.75m

3.83m

5.2.1. Background History of Ice Islands

When the leading edge of the East Ward Hunt Ice

Shelf in Ellesmere Island, west of the northern most sta-

tion Alert (Figure 5.35), broke away in 1982, Polar Shelf

decided to occupy the largest chunk of 45 m thick tabu-

lar body of ice measuring 8 km × 3 km, marked as No. 1,

in the airborne SAR image of Figure 5.36 and the aerial

photo in Figure 5.37. Recognizing its possibilities as

a moving research base, Polar Shelf actually erected a

base camp in 1984 and constructed several shelters to

accommodate research scientists. For almost 6 years,

from 1984 to 1990, PCSP base camp on ice island

was used for conducting multidisciplinary, wide‐ranging

geophysical research.

The tabular iceberg was nicknamed by the scientists

as the Hobson's Choice ice island. This name implies

the meaning “no choice.” However, there was another

deeper meaning for the name. It coincided with the con-

temporary Director of Polar Shelf, Mr. George Hobson

who played the pivotal role in the success story of Polar

Shelf and was much loved and respected by the scien-

tists, including the second author (N. K. Sinha) of this

topic. In fact, all of Sinha's efforts in training a group

of Inuit technical support persons at Pond Inlet, Baffin

Island, that led to pioneering field studies on sea ice in

Eclipse Sound [i.e.,

Sinha and Nakawo

, 1981;

Nakawo

and Sinha

, 1981] were supported financially and logisti-

cally by the Polar Shelf.

Following the separation from the East Ward Hunt ice

shelf in 1982, the ice island (Hobson's Choice) drifted

southwest in the Canada basin along the shores of the

islands for about 6 years as shown in Figure 5.35. This

drift pattern was expected to continue, but the floating

island stopped drifting after the winter of 1988-1989

and remained in the vicinity of the Meighen Ice Cap,

between Axel Heiberg Island and Ellef Ringnes Island,

until fragmented during the summer of 1990 when it

3.90m

Figure 5.34

Views of (a) polarized scattered light and (b)

cross‐polarized light of interface at a depth of 3.83 m in a core

of ice from MY ice floe.

earlier in Figures 5.22-5.24. The same characteristics also

apply to the bottom layer of ice in the MY‐R floe (origi-

nally named as 4‐PEG floe) indicated in the sketch for

texture in Figure 5.33c. Note the columnar‐grained ice

below the depth of about 4.5 m. The top surface of this

MY‐R floe had undulations with rounded and, therefore,

weathered ridges and the top 4.5 m of the ice core

exhibited typical features of an MY rubble field. It is

not possible to determine the age of this old ridge, but

microstructural analysis (shown in the sketch) clearly

indicated that this ridged rubble field formed when the

original ice sheet was about 0.5 m thick.

5.2. thE icE island ExpEriEncE

Natural ice islands in the Arctic are the massive tabular

bodies of ice that periodically break off the East Ward

Hunt Ice Shelf located on the north coast of Ellesmere

Island in the Canadian High Arctic. Ice islands are recog-

nized as hazards to offshore petroleum development in

the coastal waters of the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas.

This is because of their size and their drift and longevity

in the Arctic Ocean Beaufort Gyre. However, smaller

“man‐made sea ice islands” were also made inside the

Canadian Archipelago during the years 1975-1985, by

artificially thickening the sea ice cover, for use as off-

shore drilling platforms for oil and gas exploration [

Sinha

et al

., 1986]. These man‐made ice islands, of course, never

survived more than 1 or 2 years of summer melting and

drifted within the islands of the archipelago.