Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

Early researchers were aware that attributes such as colour and shape

are multi-dimensional and in some cases provide rich multi-attribute

examples e.g. [Ber67]; but most early researchers indicate shape as an

attribute without much elaboration and typically refer to the global form,

i.e. simple regular geometric primitives such as circles, squares, kites,

stars, teardrops, etc.

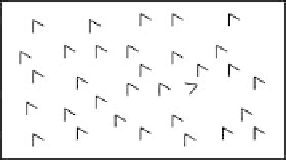

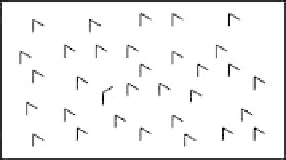

Different researchers can be ambiguous with terminology. For

example, the terms angle, slope, orientation, and collinearity refer to

orientation of different elements in a scene. In this chapter, orientation

indicates a rotational transformation upon an entire glyph within a plot,

while angle indicates the interior angle formed by edges within a singular

glyph. As shown in the table above and in the figure below (Fig 3.6),

orientation and angle should be considered two separate, independent

visual attributes.

Fig. 3.6.

Both orientation and angle can encode information. In the left image, the

only difference is the orientation of an entire single glyph. In the right image, the

only difference is the interior angle of a single glyph.

Early information visualization researchers limited the effectiveness of

shape attributes to only categorical visual tasks (with the exception of

Mazza on curvature). Pre-attentive perception researchers limit their

findings to binary tasks - either the existence of the visual attribute or not.

As shown in later examples, shape can be used to encode either categorical

data or quantitative data.

Scientific visualization

The field of scientific visualization has used shapes - particularly

curvature - for several decades as a means to convey data within a glyph.

Most of the techniques have been focused on generating smooth, curved

shapes to represent continuous quantitative data, such as tensor data. For

example (Fig. 3.7):

Search WWH ::

Custom Search