Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

12.5

10°C

10.0

1.7°C

7.2°C

7. 5

5.8°C

4.4°C

5.0

2.5

Nov

Dec

Jan eb

Mar

Apr

May

Time

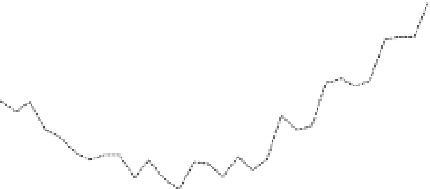

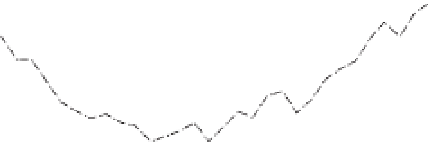

Fig. 15.2.

A typical seasonal pattern for the respiration rate of Russet Burbank tubers stored from

November to May at five temperatures from 1.7°C to 10°C. (From Dwelle and Stalknecht, 1978;

reprinted with permission from Springer Science and Business Media.)

Factors influencing respiration rates

also indicates how the respiration rate is influ-

enced by storage temperature. Immature tubers

have very high respiration rates, and these de-

crease as tubers mature (Burton, 1964; Bethke

and Busse, 2010).

Respiration rates decline most rapidly dur-

ing the first 2 months after harvest, and reach a

minimum approximately 4 months after har-

vest. Tubers of Russet Burbank harvested in

early October have been shown to reach their

minimum respiration rate around

1

February

(Fig. 15.2

). Later in storage, respiration rates

gradually increase. This increase is observed re-

gardless of whether or not sprouting occurs, but

the magnitude of the increase is less in cases

where sprouting is prevented (Isherwood and

Burton, 1975).

The temperature for minimum tuber res-

piration is approximately

5-

7°C (Schippers,

1977a; Burton, 1978). Respiration rates in-

crease as temperature increases, and the dif-

ferences between tubers stored at 4.4, 5.8, 7.2,

and 10°C may increase as storage duration in-

creases (

Fig. 15.2

). Storage below approxi-

mately 4°C also results in an increase in tuber

respiration rate compared with those stored

warmer (

5-

7°C). In

Fig. 15.2,

a large difference

in respiration rate is apparent between tubers

stored at 1.7°C and 4.4°C, regardless of time in

storage. A similar dependence of respiration

rate on temperature has been observed for

many cultivars (Schippers, 1977a).

Harvest operations and harvest damage can

have a large effect on tuber respiration rate dur-

ing the first weeks of storage, and as such can

increase dramatically the need for cooling air

during the initial storage period

(Fig. 15.3

). Res-

piration rates for cultivar Katahdin were

measured

1

or 11 days after tubers were hand

harvested, or after they had experienced one or

more mechanical harvest operations. Tubers

that had been windrowed, picked up with a

mechanical harvester, and piled into storage

had respiration rates twice those of tubers that

had been hand harvested. Each step in the har-

vest operation was additive: each contributing

to the final respiration rate

(Fig. 15.3

). Bruising,

skinning, dropping, and other mechanical stress-

es increase tuber respiration rates, which persist

for days or weeks (Schippers, 1977a; Burton, 1978;

Pisarczyk, 1982; Bethke and Busse, 2010).

Infection with pathogenic organisms leads

to an increase in the net respiration of stored po-

tatoes (Gwinn

et al

., 1989; Fennir

et al

., 2005).

The increase in tuber respiration is likely due to

the production of ethylene, exacerbated by the

infection (Creech

et al

., 1973; Gwinn

et al

.,

1989). Ethylene is a volatile plant growth regu-

lator that at very low atmospheric concentrations

(0.15 µl l

-

1

or less) stimulates potato tuber respir-

ation (Huelin and Barker, 1939; Reid and Pratt,

1972). At higher concentrations, ethylene can