Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

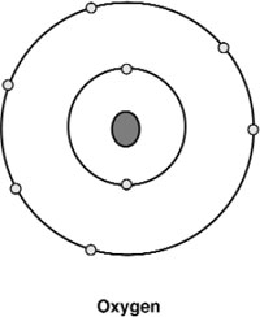

Oxygen

(Figure 19)

is the third most abundant element in the universe after hydrogen

and helium, but is the most abundant element in the Earth's crust. In very big stars—far

bigger than our own sun—oxygen nuclei can fuse to give rise to silicon, phosphorus and

sulphur, all of which have more protons than oxygen, and also an extra electron orbit

to balance the extra positive charge. Having a full inner orbit but only six electrons in

its outer shell makes oxygen passionately hungry for electrons—so hungry in fact that

it can find fulfilment by bonding covalently with virtually every single known element.

Only helium, neon, argon and krypton are immune from its fiery attentions, because

these 'noble gases' enjoy complete outer orbits and are hence serenely aloof from the

hurlyburly of the everyday soap opera of chemical life. Oxygen atoms love to bond co-

valently with each other, but in so doing a curious chemical anomaly becomes appar-

ent—two electrons from each outer orbit refuse to join the melée, and remain unpaired.

When oxygen is liquefied at very low temperatures, these free electrons make oxygen

an excellent conductor of electricity. Oxygen is the passionate Italian of the chemical

world—its urge to gather electrons is so powerful that it can literally burn up the com-

plex molecules of life, releasing copious quantities of solar energy originally locked up

by photosynthesis. Respiration, without which multicellular life, such as us, would be

impossible, uses oxygen to burn up food molecules in a gradual, controlled way and

stores the energy in special molecules such as phosphorus-rich ATP. As we saw earlier,

abundant oxygen, together with combustible gases such as methane in a planet's atmo-

sphere, are a sure sign that life is present, for only life can release vast quantities of these

gases into the air.

Figure 19: An oxygen atom with its six outer electrons.