Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

grow better in the following year, increasing their chances of becoming mature trees that

will warm the boreal region and the planet in many summers to come.

But not all winters at Isle Royale are as snowy as this one. Some years the pressure

gradient that drives the massive northward flow of moist warm air from the south weak-

ens, and little snow falls in the far north Atlantic. Then wolves hunt in smaller packs and

find it more difficult to kill moose, which thus become more numerous. More fir sap-

lings are browsed, reducing the numbers that eventually grow into large planetwarming

trees.

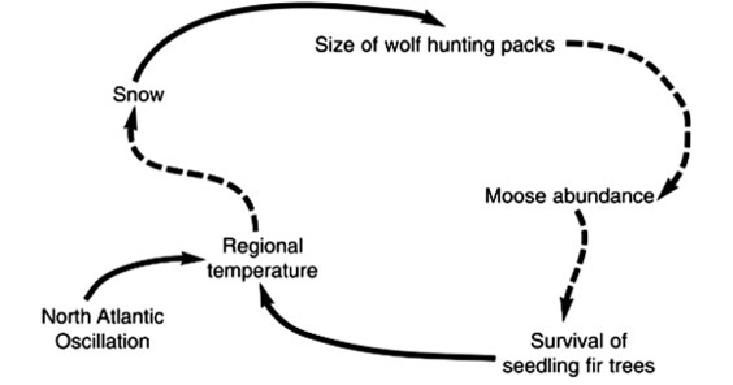

There may well be more than a mere linear chain of cause and effect running from

climate to wolves to moose to fir trees. The dark fir trees warm the boreal region and

the planet, so the chain could well bite its own tail—there might well be a feedback. By

influencing the abundance of moose and hence the cover of fir trees, it is not inconceiv-

able that wolves could influence the temperature of the boreal region and hence the very

pressure differences which lead to snowy or warm winters. The precise scientific details

of this feedback, if indeed it exists at all, may defy elucidation. Perhaps a run of snowy

winters favours hunting wolves and the growth of fir saplings so much that the trees

shoot their way into the canopy in a decade or so, warming the region with their dark,

snow-shedding branches. Once warmed, the temperature gradient down to the equatori-

al Atlantic may lessen, decreasing the chance of snow, thereby favouring the return of

the moose as wolves hunt them less effectively in the now snow-free conditions. This

begins to sound like a negative feedback with a long time constant, but no one knows. If

it exists, the feedback could look something like this

(Figure 29)

: