Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

The evolutionary trend toward large body size was perhaps

an adaptation to the cooler temperatures of the Pleistocene.

Large animals have proportionately less surface area com-

pared to their volume and thus retain heat more effectively

than do smaller animals.

In addition to mammals, some other Pleistocene ver-

tebrate animals were of impressive proportions. The giant

moas of New Zealand and the elephant birds of Madagascar

were very large, and Australia had giant birds standing 3 m

tall and weighing nearly 500 kg and a lizard 6.4 m long and

weighing 585 kg. The tar pits of Rancho La Brea in southern

California contain the remains of at least 200 kinds of ani-

mals. Many of these are fossils of dire wolves, saber-toothed

cats, and other mammals (

Equus

(Pleistocene)

Pliohippus

(Pliocene)

Figure 23.28), but some are the

remains of birds, especially birds of prey, and a giant vulture

with a wingspan of 3.6 m.

◗

Primates

are diffi cult to characterize as an order because they

lack the strong specializations found in most other mamma-

lian orders. We can, however, point to several trends in their

evolution that help defi ne primates and are related to their

ar-

boreal,

or tree-dwelling, ancestry. These include changes in the

skeleton and mode of locomotion; an increase in brain size; a

shift toward smaller, fewer, and less specialized teeth; and the

evolution of stereoscopic vision and a grasping hand with an

opposable thumb. Not all of these trends took place in every

primate group, nor did they evolve at the same rate in each

group. In fact, some primates have retained certain primitive

features, whereas others show all or most of these trends.

The primate order is divided into two suborders, the

Prosimii and Anthropoidea (Table 23.2). The

prosimians,

or

lower primates, include the lemurs, lorises, tarsiers, and tree

shrews (

Merychippus

(Miocene)

Mesohippus

(Oligocene)

Hyracotherium

(Eocene)

Figure 23.29a). They are generally small, ranging

from species the size of a mouse up to those as large as a

house cat. They are arboreal, have fi ve digits on each hand

and foot with either claws or nails, are typically omnivo-

rous, and most are nocturnal. As their name implies (

pro

means “before,” and

simian

means “ape”), they are the old-

est primate lineage, with a fossil record extending back to the

Paleocene.

◗

◗

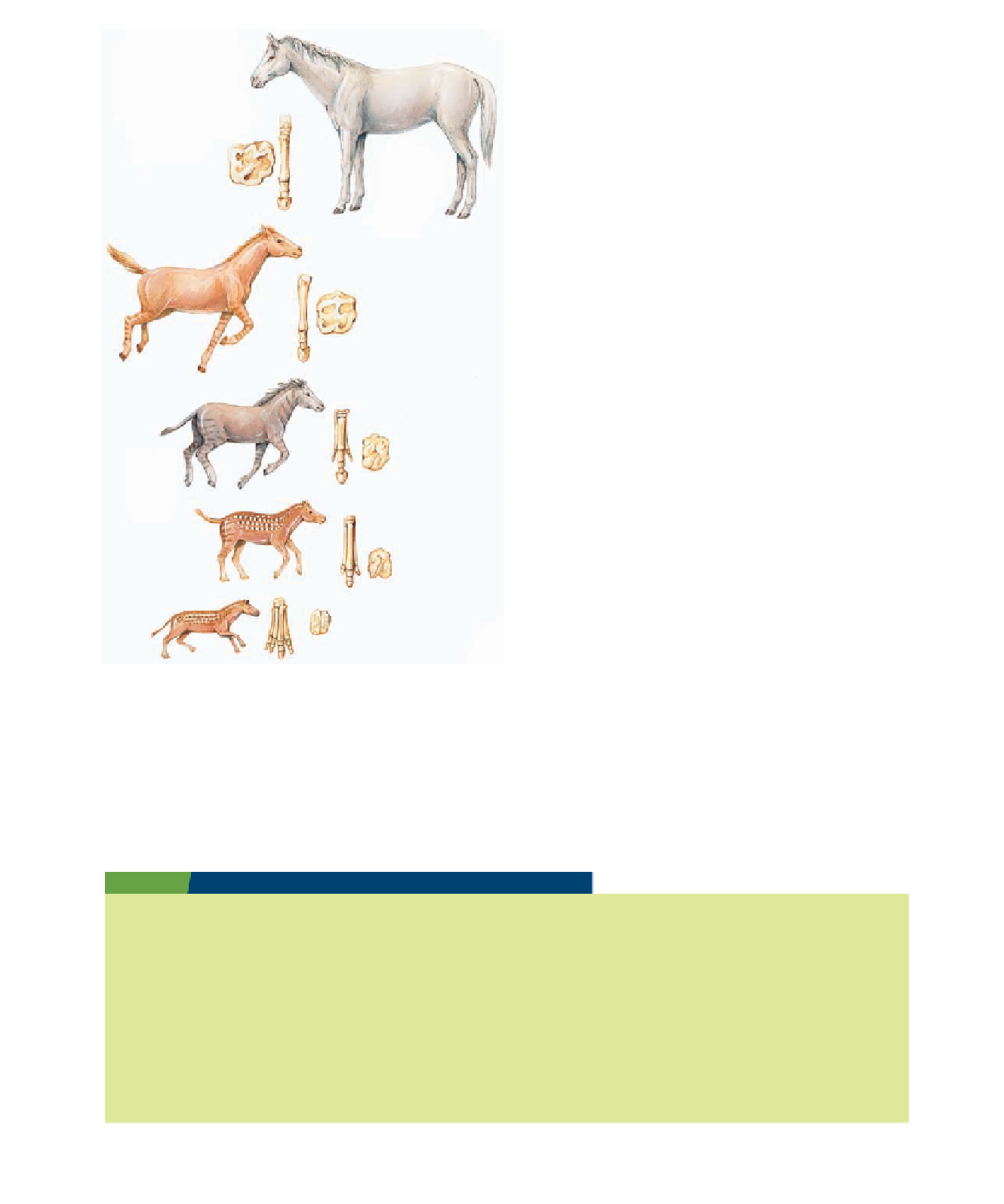

Figure 23.25

Evolution of Horses Simplifi ed diagram showing

some of the trends from the earliest known horse to the one-

toed grazing horses of the present. Trends shown include size

increase, reduction in the number of toes and lengthening of the

legs, and the development of high-crowned teeth with complex

chewing surfaces. Notice that

Merychippus

had three toes,

whereas

Pliohippus

had only one. Another evolutionary lineage

of horses, not shown here, led to the now extinct three-toed

browsers.

TABLE 23.1

Trends in the Cenozoic Evolution of the Present-Day Horse

Equus

1. Size increases.

2. Legs and feet become longer, an adaptation for running.

3. Lateral toes are reduced to vestiges. Only toe three remains functional in

Equus

.

4. The back straightens and stiffens.

5. Incisor teeth become wider.

6. Molarization of premolars yields a continuous row of teeth for grinding vegetation.

7. The chewing teeth (molars and premolars) become high-crowned and cement-covered for grinding abrasive grasses.

8. Chewing surfaces of premolars and molars become more complex, also an adaptation for grinding abrasive grasses.

9. Front part of skull and lower jaw become deeper to accommodate high-crowned premolars and molars.

10. Face in front of eye becomes longer to accommodate high-crowned teeth.

11. Brain becomes larger and more complex.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search