Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

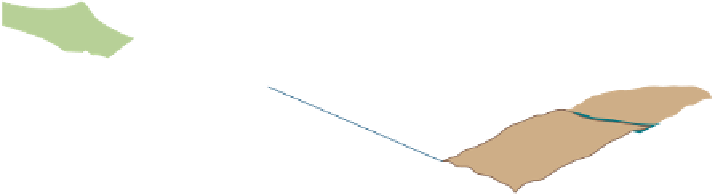

multicolored sandstones, mud-

stones, shales, and occasional lenses

of conglomerates that constitute the

world-famous

Morrison Formation

(

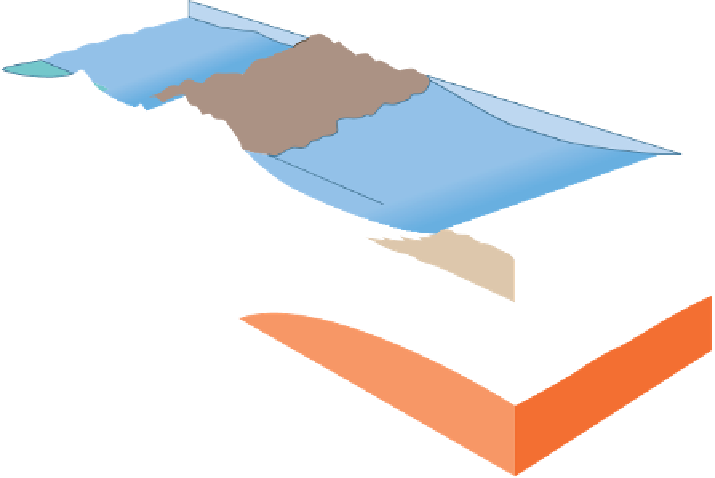

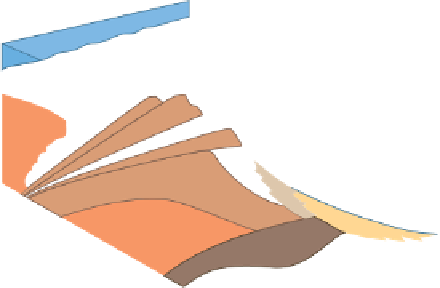

Volcanic

island arc

Sea level

California

Nevada

West

Sonoma

Mountains

Figure 22.17a).

The Morrison Formation con-

tains the world's richest assem-

blage of Jurassic dinosaur remains

(Figure 22.17b). Although most of

the dinosaur skeletons are broken up,

as many as 50 individuals have been

found together in a small area. Such

a concentration indicates that the

skeletons were brought together dur-

ing times of fl ooding and deposited

on sandbars in stream channels. Soils

in the Morrison Formation indicate

that the climate was seasonably dry.

Shortly before the end of the

Early Cretaceous, Arctic waters

spread southward over the craton,

forming a large inland sea in the

Cordilleran region. Mid-Cretaceous

transgressions also occurred on

other continents, and all were part

of the global mid-Cretaceous rise

in sea level that resulted from ac-

celerated seafl oor spreading as Pangaea continued to frag-

ment. These Middle Cretaceous transgressions are marked

by widespread black shale deposition within the oceanic

areas, the shallow sea shelf areas, and the continental re-

gions that were inundated by the transgressions.

By the beginning of the Late Cretaceous, this incursion

joined the northward-transgressing waters from the Gulf

area to create an enormous

Cretaceous Interior Seaway

that

occupied the area east of the Sevier orogenic belt. Extending

from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean, and more than

1500 km wide at its maximum extent, this seaway effectively

divided North America into two large landmasses until just

before the end of the Late Cretaceous (Figure 22.6).

Cretaceous deposits less than 100 m thick indicate that

the eastern margin of the Cretaceous Interior Seaway sub-

sided slowly and received little sediment from the emergent,

low-relief craton to the east. The western shoreline, however,

shifted back and forth, primarily in response to fl uctuations

in the supply of sediment from the Cordilleran Sevier oro-

genic belt to the west. The facies relationships show lateral

changes from conglomerate and coarse sandstone adjacent to

the mountain belt through fi ner sandstones, siltstones, shales,

and even limestones and chalks in the east. During times of

particularly active mountain building, these coarse clastic

wedges of gravel and sand prograded even farther east.

As the Mesozoic Era ended, the Cretaceous Interior Sea-

way withdrew from the craton. During this regression, ma-

rine waters retreated to the north and south, and marginal

marine and continental deposition formed widespread coal-

bearing deposits on the coastal plain.

◗

Craton

East

Oceanic crust

Antler orogenic belt

and associated thrust faults

Continental crust

Upper mantle

◗

Figure 22.8

Sonoma Orogeny Tectonic activity that culminated in the Permian-Triassic

Sonoma orogeny in western North America. The Sonoma orogeny was the result of a collision

between the southwestern margin of North America and an island arc system.

These rocks represent a variety of continental deposi-

tional environments. The Upper Triassic

Chinle Formation,

for

example, is widely exposed throughout the Colorado Plateau

region and is probably most famous for its petrifi ed wood spec-

tacularly exposed in Petrifi ed Forest National Park, Arizona

(

Figure 22.15). This formation, as well as other Triassic

formations in the Southwest, also contains the fossilized re-

mains and tracks of various amphibians and reptiles.

Early Jurassic-age deposits in a large part of the west-

ern region consist mostly of clean, cross-bedded sand-

stones indicative of wind-blown deposits. The thickest

and most prominent of these is the

Navajo Sandstone,

a

widespread cross-bedded sandstone that accumulated in a

coastal dune environment along the southwestern margin

of the craton. The sandstone's most distinguishing feature

is its large-scale cross-beds, some of which are more than

25 m high (

◗

Figure 22.16).

Marine conditions returned to the region during the Mid-

dle Jurassic when a wide seaway called the

Sundance Sea

twice

fl ooded the interior of western North America (Figure 22.5).

The resulting deposits, the

Sundance Formation,

were produced

from erosion of tectonic highlands to the west that paralleled

the shoreline. These highlands resulted from intrusive igneous

activity and associated volcanism that began during the Triassic.

During the Late Jurassic, a mountain chain formed

in Nevada, Utah, and Idaho as a result of the deforma-

tion produced by the Nevadan orogeny. As the mountain

chain grew and shed sediments eastward, the Sundance Sea

began retreating northward. A large part of the area for-

merly occupied by the Sundance Sea was then covered by

◗

Search WWH ::

Custom Search