Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

basins constantly changes. One

of the goals of historical geology

is to provide paleogeographic

reconstructions of the world

during the geologic past. By

synthesizing all of the pertinent

paleoclimatic, paleomagnetic,

paleontologic, sedimentologic,

stratigraphic, and tectonic data

available, geologists can con-

struct paleogeographic maps.

Such maps are simply interpreta-

tions of the geography of an area

for a particular time in the geo-

logic past and usually show the

distribution of land and sea, pos-

sible climatic regimes, and such

geographic features as mountain

ranges, swamps, and glaciers.

The paleogeographic history

of the Paleozoic Era, for example,

is not as precisely known as that of

the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras, in

part because the magnetic anomaly

patterns preserved in the oceanic

crust were destroyed when much

of the Paleozoic oceanic crust was

subducted during the formation

of Pangaea. Paleozoic paleogeo-

graphic reconstructions are there-

fore based primarily on structural

relationships, climate-sensitive

sediments such as red beds, evapo-

rites, and coals, as well as the distri-

bution of plants and animals.

At the beginning of the Paleozoic, six major conti-

nents were present. Besides these large landmasses, geolo-

gists have also identifi ed numerous microcontinents, such

as

Avalonia

(composed of parts of present-day Belgium,

northern France, England, Wales, Ireland, the Maritime

Provinces and Newfoundland of Canada, as well as parts

of the New England area of the United States), and various

island arcs associated with microplates. We are primarily

concerned, however, with the history of the six major conti-

nents and their relationships to one another. The six major

Paleozoic continents are

Baltica

(Russia west of the Ural

Mountains and the major part of northern Europe),

China

(a complex area consisting of at least three Paleozoic conti-

nents that were not widely separated and are here consid-

ered to include China, Indochina, and the Malay Peninsula),

Gondwana

(Africa, Antarctica, Australia, Florida, India, Mad-

agascar, and parts of the Middle East and southern Europe),

Kazakhstania

(a triangular continent centered on Kazakh-

stan but considered by some to be an extension of the

Paleozoic Siberian continent),

Laurentia

(most of present-

day North America, Greenland, northwestern Ireland, and

Franklin

mobile

belt

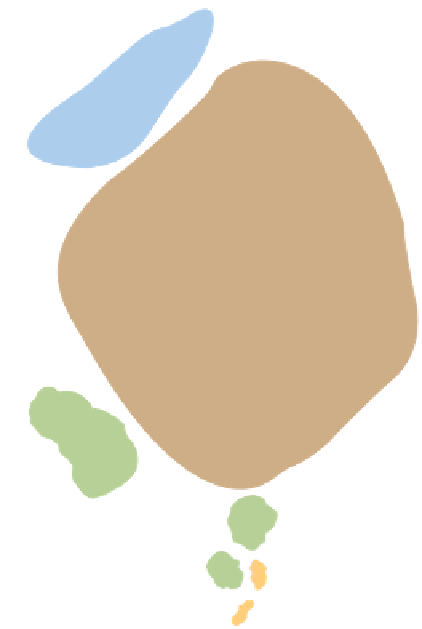

Canadian

Shield

Williston

Basin

Appalachian

Basin

Michigan Basin

Cincinnati Arch

Illinois Basin

Nemaha Ridge

Platform

Ozark Dome

Nashville

Dome

Permian

Basin

Ouachita

mobile

belt

◗

Figure 20.1

Major Cratonic Structures and Mobile Belts The major cratonic structures

and mobile belts of North America that formed during the Paleozoic Era.

Mobile belts

are elongated areas of mountain-building

activity. They are located along the margins of continents

where sediments are deposited in the relatively shallow

waters of the continental shelf and the deeper waters at the

base of the continental slope. During plate convergence along

these margins, the sediments are deformed and intruded by

magma, creating mountain ranges.

Four mobile belts formed around the margin of the

North American craton during the Paleozoic: the

Frank-

lin, Cordilleran, Ouachita

, and

Appalachian mobile belts

(Figure 20.1). Each was the site of mountain building in

response to compressional forces along a convergent plate

boundary and formed mountain ranges such as the Appala-

chians and Ouachitas.

One result of plate tectonics is that Earth's geography is

constantly changing. The present-day confi guration of the

continents and ocean basins is merely a snapshot in time. As

the plates move about, the location of continents and ocean

Search WWH ::

Custom Search