Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

the result of organic activity. In fact, stromatolites still form

in a few areas where they originate by trapping sediment on

sticky mats of photosynthesizing cyanobacteria, more com-

monly known as blue-green algae (

metabolic process developed, probably

fermentation,

an anaer-

obic process during which molecules such as sugars are split

and release carbon dioxide, alcohol, and energy. As a matter of

fact, most living prokaryotes practice fermentation.

Of course, the nature of the earliest cells is informed

speculation, but we can say that the most signifi cant event in

Archean life history was the development of the autotrophic

process of photosynthesis. These more advanced cells were

still anaerobic and prokaryotic, but as autotrophs they no

longer depended on an external source of preformed organic

molecules for their nutrients. The Archean fossil in Figure 19.20

belongs to the kingdom Monera, which is represented today by

bacteria, cyanobacteria, and archaea.

Figure 19.19). Although

widespread in Proterozoic rocks, they are now restricted to

aquatic environments with especially high salinity where

snails cannot live and graze on them.

Currently, the oldest known stromatolites are from

3.0-billion-year-old rocks in South Africa, but other prob-

able ones have been discovered in 3.3- to 3.5-billion-year-old

rocks near North Pole, Australia. Even more ancient evidence

comes from 3.8-billion-year-old rocks in Greenland that

have tiny particles of carbon that indicate organic activity,

perhaps photosynthesis; but the evidence is not conclusive.

Cyanobacteria, the oldest known fossils, practice photo-

synthesis, a complex metabolic process that must have been

preceded by a simpler process. So it seems reasonable that

cyanobacteria were preceded by nonphotosynthesizing or-

ganisms for which we so far have no fossils. They probably

resembled tiny bacteria, and because the atmosphere lacked

free oxygen, they were

anaerobic

, meaning they required no

free oxygen. They also were probably

heterotrophic,

depen-

dent on an external source of nutrients, rather than

auto-

trophic,

capable of manufacturing their own nutrients as in

photosynthesis. And fi nally, they were

prokaryotic cells,

cells

lacking a cell nucleus and other internal structures typical of

more advanced

eukaryotic cells

(discussed in a later section).

We can characterize these earliest organisms as single-

celled, anaerobic, heterotrophic prokaryotes (

◗

The Paleoproterozoic, like the Archean, is characterized

mostly by a biota of single-celled, prokaryotic bacteria and

cyanobacteria. No doubt thousands of varieties existed, but

none of the more familiar organisms such as plants and ani-

mals were present. Before the appearance of cells capable of

sexual reproduction, evolution was a comparatively slow

process, accounting for the low organic diversity.

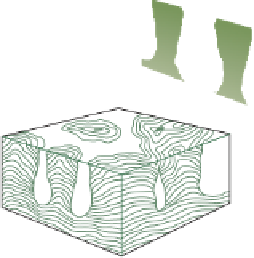

A New Type of Cell Appears

The origin of

eukaryotic

cells

marks one of the most important events in life history

(Table 19.1). These cells are much larger than prokaryotic cells;

they have a membrane-bounded nucleus containing the genetic

material, and most reproduce sexually (

Figure 19.20).

Furthermore, they reproduced asexually. Their energy source

was probably adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which can be syn-

thesized from simple gases and phosphate, so it was no doubt

available in the early Earth environment. These cells may have

simply acquired their ATP directly from their surroundings,

but this situation could not have persisted for long because

as more and more cells competed for the same resources, the

supply should have diminished. Thus, a more sophisticated

◗

Figure 19.21). And

many eukaryotes—that is, organisms made up of eukaryotic

cells—are multicellular and aerobic, so they could not have existed

until some free oxygen was present in the atmosphere.

No one doubts that eukaryotes were present by the

Mesoproterozoic. Currently, the oldest known eukaryote is

Bangiomorph

from 1.2-billion-year-old rocks in Canada; it

was multicelled and reproduced sexually. Other Proterozoic

rocks have yielded fossils of unknown affi nities. For example,

◗

◗

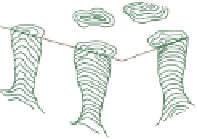

Figure 19.19

Stromatolites

b

Different types of stromatolites include irregular mats, columns,

and columns linked by mats.

a

Present-day stromatolites, Shark Bay, Australia.

Source:

b

R.L. Anstey and T.L. Chase,

Environments Through Time

, 1974, MacMillan Publishing Company.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search