Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

◗

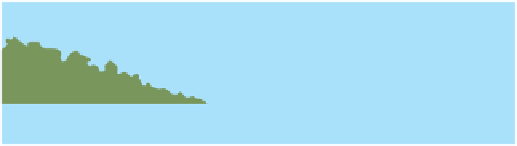

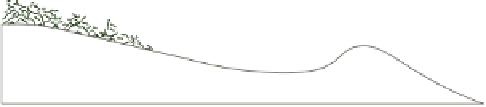

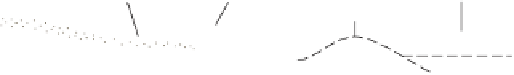

Figure 16.20

Barrier Island Migration

Isle of

Wight Bay

Fenwick

Island

N

Lagoon

Barrier island

a

A barrier island.

Ocean City

Jetty

Ocean City

Inlet

MARYLAND

Sea level

rise

Upper

Sinepuxent

Neck

Atlantic Ocean

Position of

shoreline

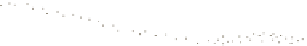

b

A barrier island migrates landward as sea level rises and storm

waves carry sand from its seaward side into its lagoon.

1980

1849

Assateague

Island

0

2

1

Migrating

barrier island

Original

barrier island

position

Sea level

rise

km

Lagoon

d

Jetties were constructed during the 1930s to protect the inlet at

Ocean City, Maryland, but they disrupted the net southerly longshore

drift and Assateague Island, starved of sediment, has migrated

500 m landward. Beginning in the fall of 2002, beach sand was

artifi cially replenished in an effort to stabilize the island.

Barrier island movement

c

Over time, the entire island shifts toward the land.

being lost at a rate of about 90 km

2

per year. Much of this loss

results from sediment compaction, but rising sea level exacer-

bates the problem.

Another consequence of Hurricane Katrina was its ef-

fect on the Chandeleur Islands, off of Louisiana's southeast

coast (

Gulf Coasts, but would cover 20% of the entire country

of Bangladesh. Other problems associated with rising sea

level include increased coastal fl ooding during storms and

saltwater incursions that may threaten groundwater sup-

plies (see Chapter 13).

Armoring shorelines with

seawalls

(embankments

of reinforced concrete or stone) (Figure 16.18) and using

riprap

(piles of stones,

Figure 16.21). These are barrier islands that ab-

sorb some of the impact of approaching storms, especially

storm surges. When Hurricane Katrina swept across this

area, the islands were battered and reduced to small shoals

(Figure 16.21).

Rising sea level also directly threatens many beaches

upon which communities depend for revenue. The beach

at Miami Beach, Florida, for instance, was disappearing

at an alarming rate until the Army Corps of Engineers

began replacing the eroded beach sand. The problem is

even more serious in other countries. A rise in sea level of

only 2 m would inundate large areas of the U.S. East and

◗

Figure 16.22a) protect beachfront

structures, but both are initially expensive and during large

storms are commonly damaged or destroyed. Seawalls do

afford some protection and are seen in many coastal areas

along the oceans and large lakes, but some states, includ-

ing North and South Carolina, Rhode Island, Oregon, and

Maine, no longer allow their construction. The futility of

artificially maintaining beaches is aptly shown by efforts

to protect homes on a South Carolina barrier island. After

each spring tide, heavy equipment builds a sand berm to

◗

Search WWH ::

Custom Search