Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

Moist

marine air

Warm

dry air

Rain-shadow

desert

◗

Figure 15.18

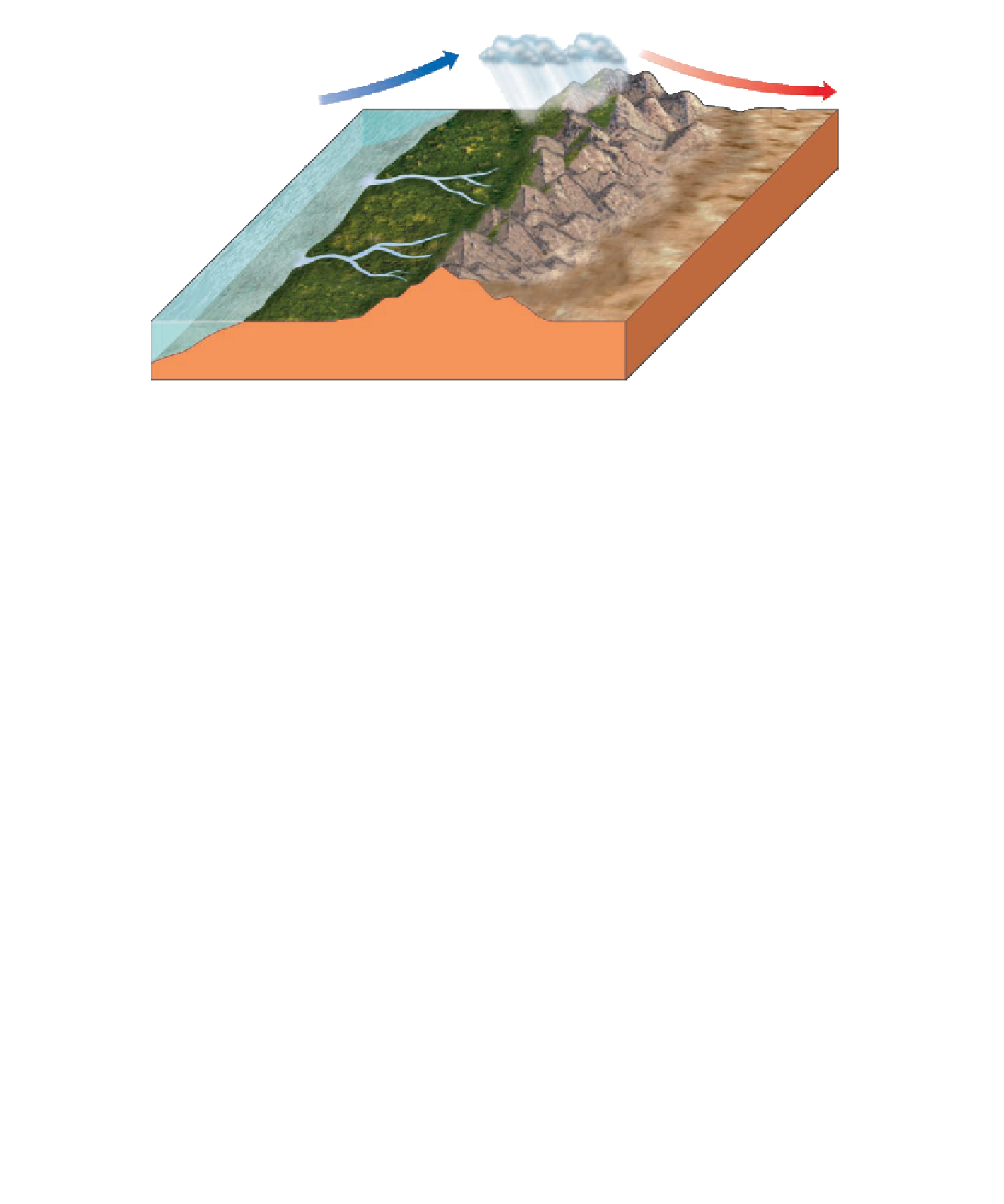

Rain-Shadow Deserts Many deserts in the middle and high latitudes are rain-shadow

deserts, so named because they form on the leeward side of mountain ranges. When moist marine

air moving inland meets a mountain range, it is forced upward, where it cools and forms clouds that

produce rain. This rain falls on the windward side of the mountains. The air descending on the leeward

side is much warmer and drier, producing a rain-shadow desert.

of mountain ranges that produce a

rain-shadow desert

(

pavement, or sand dunes. Yet despite the great contrast

between deserts and more humid areas, the same geo-

logic processes are at work, only operating under different

climatic conditions.

Figure 15.18). When moist marine air moves inland and

meets a mountain range, it is forced upward. As it rises, it

cools, forming clouds and producing precipitation that falls

on the windward side of the mountains. The air that de-

scends on the leeward side of the mountain range is much

warmer and drier, producing a rain-shadow desert.

Three widely separated areas are included within the

mid-latitude dry-climate zone (Figure 15.17). The largest

is the central part of Eurasia, extending from just north of

the Black Sea eastward to north-central China. The Gobi

Desert in China is the largest desert in this region. The

Great Basin area of North America is the second largest

mid-latitude dry-climate zone and results from the rain

shadow produced by the Sierra Nevada. This region adjoins

the southwestern deserts of the United States that formed

as a result of the low-latitude subtropical high-pressure

zone. The smallest of the mid-latitude dry-climate areas is

the Patagonian region of southern and western Argentina.

Its dryness results from the rain-shadow effect of the An-

des. The remainder of the world's deserts are found in the

cold but dry high latitudes, such as Antarctica.

◗

The heat and dryness of deserts are well known. Many of the

deserts of the low latitudes have average summer temperatures

that range between 32° and 38°C. It is not uncommon for

some low-elevation inland deserts to record daytime highs of

46° to 50°C for weeks at a time. The highest temperature ever

recorded was 58°C in El Azizia, Libya, on September 13, 1922.

During the winter months when the Sun's angle is lower

and there are fewer daylight hours, daytime temperatures

average between 10° and 18°C. Winter nighttime lows can

be cold, with frost and freezing temperatures common in

the more poleward deserts. Winter daily temperature fl uc-

tuations in low-latitude deserts are among the greatest in the

world, ranging between 18° and 35°C. Temperatures have

been known to fl uctuate from below 0°C to higher than 38°C

in a single day!

The dryness of the low-latitude deserts results primar-

ily from the year-round dominance of the subtropical high-

pressure belt, whereas the dryness of the mid-latitude deserts

is due to their isolation from moist marine winds and the

rain-shadow effect created by mountain ranges. The dryness

of both is accentuated by their high temperatures.

Although deserts are defi ned as regions that receive, on

average, less than 25 cm of rain per year, the amount of rain

To people who live in humid regions, deserts may seem

stark and inhospitable. Instead of a landscape of roll-

ing hills and gentle slopes with an almost continuous

cover of vegetation, deserts are dry, have little vegetation,

and consist of nearly continuous rock exposures, desert

Search WWH ::

Custom Search