Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

?

What Would You Do

After carefully observing the same valley glacier for several

years, you conclude (1) that its terminus has retreated at

least 1 km and (2) that debris on its surface have obviously

moved several hundreds of meters toward the glacier's termi-

nus. Can you think of an explanation for these observations?

Also, why do you think studying glaciers might have some im-

plications for the debate on global warming?

for “rock sheep.” As shown in

Figure 14.9, a glacier

smooths the “upstream” side of an obstacle, such as a small

hill, and plucks pieces of rock from the “downstream”

side by repeatedly freezing to and pulling away from the

obstacle.

Bedrock over which sediment-laden glacial ice moves

is effectively eroded by

abrasion

and develops a

glacial

polish,

a smooth surface that glistens in reflected light

(

◗

◗

Figure 14.8

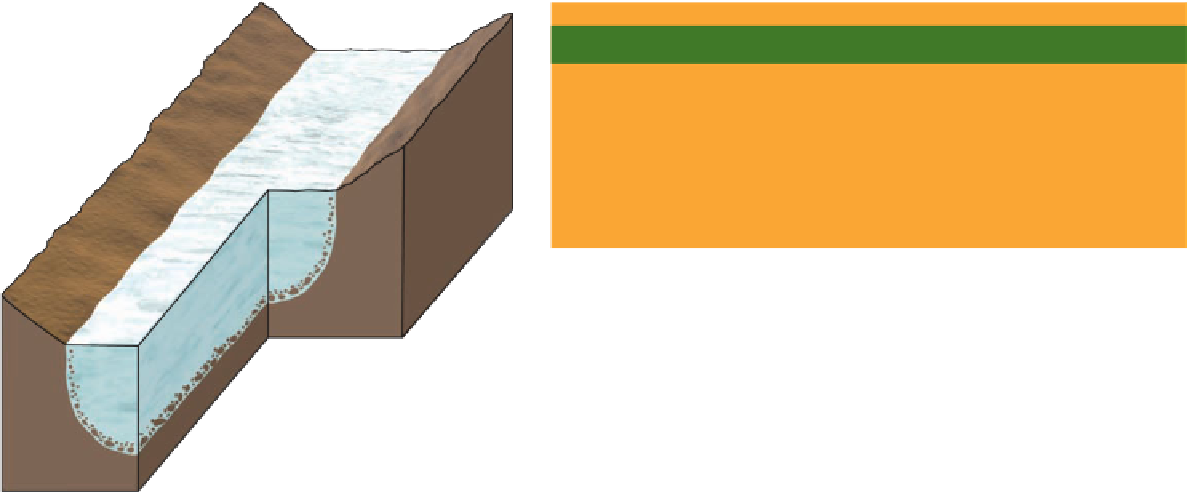

Flow Velocity in a Valley Glacier Flow velocity in

a valley glacier varies both horizontally and vertically. Velocity is

greatest at the top center of the glacier because friction with the

walls and fl oor of the trough slows the fl ow adjacent to these

boundaries. The lengths of the arrows in the fi gure are proportional

to velocity.

Figure 14.10a). Abrasion also yields

glacial striations,

consisting of rather straight scratches rarely more than

a few millimeters deep on rock surfaces. Abrasion thor-

oughly pulverizes rocks, yielding an aggregate of clay- and

silt-sized particles that have the consistency of flour—

hence, the name

rock flour

. Rock flour is so common in

streams discharging from glaciers that the water has a

milky appearance (Figure 14.10b).

Continental glaciers derive sediment from mountains

projecting through them, and wind-blown dust settles on

their surfaces, but most of their sediment comes from the

surface they move over. As a result, most sediment is trans-

ported in the lower part of the ice sheet. In contrast, valley

glaciers carry sediment in all parts of the ice, but it is con-

centrated at the base and along the margins (

◗

soft sediment beneath a glacier squeezes fl uids through the

sediment, thereby allowing the overlying glacier to slide

more effectively.

BY GLACIERS

As moving solids, glaciers erode, transport, and eventually

deposit huge quantities of sediment and soil. Indeed, they

have the capacity to transport any size of sediment, includ-

ing boulders the size of houses, as well as clay-sized particles.

Important processes of erosion include bulldozing, pluck-

ing, and abrasion.

Although

bulldozing

is not a formal geologic term, it

is fairly self-explanatory; glaciers shove or push unconsoli-

dated materials in their paths. This effective process was aptly

described in 1744 during the Little Ice Age by an observer in

Norway:

Figure 14.11).

Some of the marginal sediment is derived by abrasion and

plucking, but much of it is supplied by mass wasting pro-

cesses, as when soil, sediment, or rock falls or slides onto the

glacier's surface.

◗

When mountain ranges are eroded by valley glaciers, they take

on a unique appearance of angular ridges and peaks in the midst

of broad, smooth valleys with near-vertical walls. The erosional

landforms produced by valley glaciers are easily recognized and

enable us to appreciate the tremendous erosive power of mov-

ing ice. See Geo-inSight on pages 370 and 371 which features

U-shaped glacial troughs, fjords, hanging valleys, cirques, arêtes,

and horns.

U-Shaped Glacial Troughs

A

U-shaped glacial trough

is one of the most distinctive features of valley glaciation.

Mountain valleys eroded by running water are typically

V-shaped in cross section; that is, they have valley walls that

descend to a narrow valley bottom (

When at times [the glacier] pushes forward a great

sound is heard, like that of an organ and it pushes

in front of it unmeasurable masses of soil, grit and

rocks bigger than any house could be, which it then

crushes small like sand.*

Plucking

, also called

quarrying

, results when glacial ice

freezes in the cracks and crevices of a bedrock projection

and eventually pulls it loose. One manifestation of pluck-

ing is a landform called a

roche moutonnée

, a French term

Figure 14.12a). In con-

trast, valleys scoured by glaciers are deepened, widened, and

straightened so that they have very steep or vertical walls, but

◗

*Quoted in C. Offi cer and J. Page,

Tales of the Earth

(New York: Oxford

University Press, 1993), p. 99.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search