Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

surfaces they move over, producing many easily recogniz-

able landforms, and they deposit huge amounts of sediment,

much of it important sources of sand and gravel. Glaciers

today cover about 10% of Earth's land surface, but during the

Ice Age they were much more widespread.

Studying glaciers and their possible causes may clarify

some aspects of long-term climatic change and the debate

on global warming (see Geo-Focus on pages 364 and 365).

Glaciers are very sensitive to even short-term changes in cli-

mate, so scientists closely monitor them to see whether they

advance, remain stationary, or retreat.

defi nition are

moving

and

on land

. Accordingly, permanent

snowfi elds in high mountains, though on land, are not gla-

ciers because they do not move. All glaciers share several

characteristics, but they differ enough in size and location

for geologists to defi ne two specifi c types, valley glaciers and

continental glaciers, and several subvarieties.

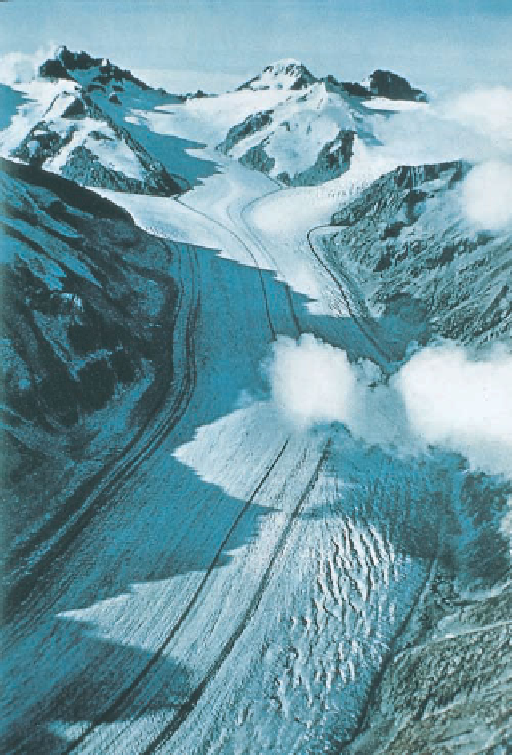

Valley glaciers are confi ned to mountain valleys where they

fl ow from higher to lower elevations (

Figure 14.2), whereas

continental glaciers cover vast areas, they are not confi ned

by the underlying topography, and they flow outward in

all directions from areas of snow and ice accumulation. We

use the term

valley glacier,

but some geologists prefer the

synonyms

alpine glacier

and

mountain glacier

. Valley gla-

ciers commonly have tributaries, just as streams do, thereby

forming a network of glaciers in an interconnected system

of mountain valleys.

Valley glaciers are common in the mountains of western

North America, especially Alaska and Canada, as well as the

Andes in South America, the Alps in Europe, the Alps of New

Zealand, and the Himalayas in Asia. Even a few of the loft-

ier mountains in Africa, though near the equator, are high

enough to support small glaciers. In fact, Australia is the only

continent that has no glaciers.

A valley glacier's shape is obviously controlled by the

shape of the valley it occupies, so it tends to be a long, nar-

row tongue of moving ice. Valley glaciers that fl ow into the

ocean are called

tidewater glaciers

; they differ from other val-

ley glaciers only in that their terminus is in the sea rather

than on land (Figure 14.2b).

Valley glaciers are small compared with the much more

extensive continental glaciers, but even so, they may be as

large as several kilometers across, 200 km long, and hundreds

of meters thick. Some glaciers in Alaska are up to 1500 m

thick. Erosion and deposition by valley glaciers were responsible

for much of the spectacular scenery in several U.S. and Cana-

dian national parks, notably Yosemite, Glacier, and Banff-Jasper.

◗

Geologists defi ne a

glacier

as a moving body of ice on land

that flows downslope or outward from an area of accu-

mulation. We will discuss how glaciers fl ow in a later sec-

tion. Our definition of a glacier excludes frozen seawater

as in the North Polar region, and sea ice that forms yearly

adjacent to Greenland and Iceland. Drifting icebergs are not

glaciers either, although they may have come from glaciers

that fl owed into lakes or the sea. The critical points in the

◗

Figure 14.2

Valley Glaciers

b

Wellesley Glacier in Alaska fl ows into the sea, so it is a tidewater

glacier.

a

A valley glacier in Alaska. Notice the tributaries that unite to

form a larger glacier.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search