Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

from areas where the water table is high toward areas where it

is lower, such as streams, lakes, or swamps. Only some of the

water follows the direct route along the slope of the water table.

Most of it takes longer curving paths down and then enters a

stream, lake, or swamp from below, because it moves from ar-

eas of high pressure toward areas of lower pressure within the

saturated zone.

Groundwater velocity varies greatly and depends on

many factors. Velocities range from 250 m per day in some

extremely permeable material to less than a few centimeters

per year in nearly impermeable material. In most ordinary

aquifers, the average velocity of groundwater is a few

centimeters per day.

swamps, where it discharges at the surface as

springs

, and

where it is withdrawn from the system at water wells.

Places where groundwater fl ows or seeps out of the ground

as

springs

have always fascinated people. The water fl ows out

of the ground for no apparent reason and from no readily

identifi able source. So it is not surprising that springs have

long been regarded with superstition and revered for their

supposed medicinal value and healing powers. Nevertheless,

there is nothing mystical or mysterious about springs.

Although springs can occur under a wide variety of

geologic conditions, they all form in basically the same way

(

Figure 13.4a). When percolating water reaches the water

table or an impermeable layer, it fl ows laterally, and if this

fl ow intersects the surface, the water discharges as a spring

(Figure 13.4b). The Mammoth Cave area in Kentucky is

underlain by fractured limestones whose fractures have been

enlarged into caves by solution activity. In this geologic envi-

ronment, springs occur where the fractures and caves inter-

sect the ground surface, allowing groundwater to exit onto

the surface. Most springs are along valley walls where streams

have cut valleys below the regional water table.

Springs can also develop wherever a perched water table

intersects the surface (Figure 13.3). A

perched water table

may

occur wherever a local aquiclude is present within a larger

aquifer, such as a lens of shale within sandstone. As water

migrates through the zone of aeration, it is stopped by the

local aquiclude, and a localized zone of saturation “perched”

◗

AND ARTESIAN SYSTEMS

You can think of the water in the zone of saturation much

like a reservoir whose surface rises or falls depending on

additions as opposed to natural and artifi cial withdrawals.

Recharge

—that is, additions to the zone of saturation—

comes from rainfall or melting snow, or water might

be added artificially at wastewater-treatment plants or

recharge ponds constructed for just this purpose. But if

groundwater is discharged naturally or withdrawn at wells

without sufficient recharge, the water table drops just as a

savings account diminishes if withdrawals exceed depos-

its. Withdrawals from the groundwater system take place

where groundwater flows laterally into streams, lakes, or

◗

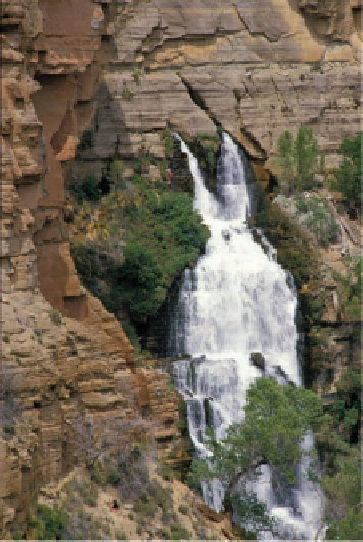

Figure 13.4

Springs Springs form wherever laterally moving

groundwater intersects Earth's surface.

Springs

Permeable

sandstone

beds

Impermeable

shale beds

a

Most commonly, springs form when percolating water reaches an

impermeable layer and migrates laterally until it seeps out at the surface.

b

Thunder River Spring in the Grand Canyon, Arizona, issues from

rocks along a wall of the Grand Canyon. Water percolating downward

through permeable rocks is forced to move laterally when it encounters

an impermeable zone, and thus gushes out along this cliff. Notice the

vegetation parallel to and below the springs, indicating enough water

fl ows from springs along the cliff wall to support the vegetation.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search