Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

◗

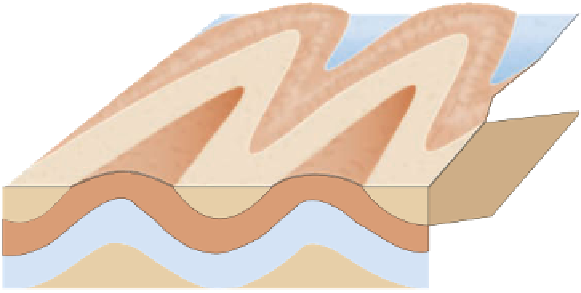

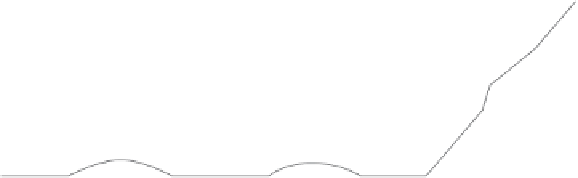

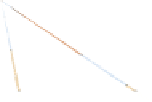

Figure 10.12

Plunging Folds

Axial

plane

Youngest exposed rocks

Oldest

exposed

rocks

Angle of

plunge

Axis

Plunging

anticline

Plunging

syncline

Plunging

anticline

a

A plunging fold.

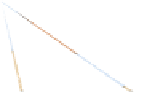

b

Surface and cross-sectional views of plunging folds. The long arrow is

the geologic symbol for a plunging fold; it shows the direction of plunge.

Image not available due to copyright restrictions

western margin of the Basin and Range is bounded by nor-

mal faults, and the range has risen along these faults so that

it now stands more than 3000 m above the lowlands to the

east (see Chapter 23). Also, an active normal fault is found

along the eastern margin of the Teton Range in Wyoming,

accounting for the 2100-m elevation difference between

the valley floor and the highest peaks in the mountains

(

kilometers.) On this fault, a huge slab of Precambrian-age

rocks moved at least 75 km eastward and now rests upon

much younger Cretaceous-aged rocks (see Geo-inSight on

pages 262 and 263).

Strike-Slip Faults

Strike-slip faults

, resulting from

shear stresses, show horizontal movement with blocks

on opposite sides of the fault sliding past one another

(Figure 10.3c; Figure 10.16d). In other words, all movement

is in the direction of the fault plane's strike—hence the

name

strike-slip

fault. Several large strike-slip faults are

known, but the best studied is the San Andreas fault, which

cuts through coastal California. Recall from Chapter 2 that

the San Andreas fault is called a

transform fault

in plate

tectonics terminology.

Figure 10.17).

Reverse and thrust faults result from compression

(Figure 10.3a; Figure 10.16b, c). Large-scale examples of

both are found in mountain ranges that formed at con-

vergent plate margins, where one would expect compres-

sion (discussed later in this chapter). A well-known thrust

fault is the Lewis overthrust of Montana. (An overthrust

is a low-angle thrust fault with movement measured in

◗

Search WWH ::

Custom Search