Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

radon gas.

Geologic

hazards

account for

thousands

of fatalities

and billions

of dollars in

property dam-

age every year,

and whereas

the incidence

of hazards has

not increased,

fatalities and

damages have

grown because

more and

more people

live in disaster-

prone areas.

We cannot eliminate geologic

hazards, but we can better understand

these events, design structures to pro-

tect shoreline communities and with-

stand shaking during earthquakes, enact

zoning and land-use regulations, and,

at the very least, decrease the amount

of damage and human suffering.

Unfortunately, geologic

information that is readily available

is often ignored or overlooked.

A case in point is the Turnagain

Heights subdivision in Anchorage,

Alaska, that was so heavily damaged

when the soil liquefied during the

1964 earthquake (see Figure 14.19).

Not only were reports on soil stabil-

ity ignored or overlooked before

homes were built there, but since

1964, new homes were built on part

of the same site!

In many mountainous or even

hilly areas, highways are notoriously

unstable and slump or slide from hill-

sides. When this happens, engineering

geologists are consulted for their rec-

ommendations for stabilizing slopes.

They may suggest building retaining

walls or drainage systems to keep the

slopes dry, planting vegetation, or, in

some cases, simply rerouting the high-

way if it is too costly to maintain in its

present position.

As you read the following chapters

on surface processes, keep in mind

that engineering geologists are in-

volved in many aspects of stabilizing

slopes, designing and constructing

dams and fl ood-control projects, and

building structures to protect seaside

communities.

◗

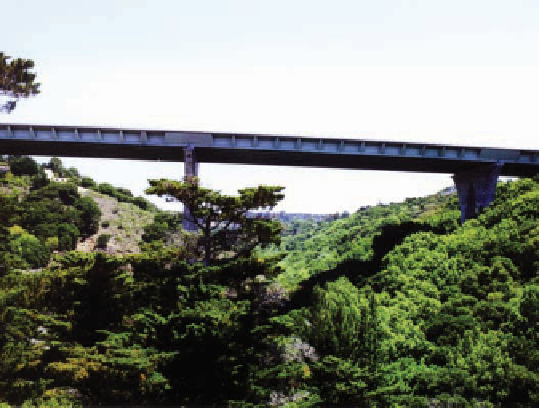

Figure 2

This freeway crosses a small valley a short distance from

the San Andreas fault in California. Engineers had to take into account

the near certainty that this structure would be badly shaken during an

earthquake.

information that can be incorporated

into engineering practice to make free-

ways, buildings, and bridges safer dur-

ing earthquakes.

Natural hazards include wildfi res,

swarms of insects, and severe weather

phenomena, as well as various geologic

hazards such as fl ooding, landslides,

volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, tsu-

nami, land subsidence, soil creep, and

and sets of joints are usually related to other geologic struc-

tures such as large folds and faults.

We have discussed columnar joints that form when lava

or magma in some shallow plutons cools and contracts (see

Figure 5.6). A different type of jointing previously discussed

is sheet jointing that forms in response to pressure release

(see Figure 6.4).

Another type of fracture known as a

fault

is one along which

blocks of rock on opposite sides of the fracture have moved

parallel with the fracture surface, and the surface along which

movement takes place is a

fault plane

(

plane, the rocks on opposite sides may be scratched and pol-

ished or crushed and shattered into angular blocks, forming

fault breccia

(Figure 10.15c).

Notice the designations

hanging wall block

and

footwall

block

in Figure 10.15a

.

The

hanging wall block

consists of

the rock overlying the fault, whereas the

footwall block

lies

beneath the fault plane. You can recognize these two blocks

on any fault except a vertical one—that is, one that dips at

90 degrees. To identify some kinds of faults, you must not

only correctly identify these two blocks, but also determine

which one moved relatively up or down. We use the phrase

relative movement

because you cannot usually tell which

block moved or if both moved. In Figure 10.15a, the footwall

block may have moved up, the hanging wall block may have

moved down, or both could have moved. Nevertheless, the

hanging wall block appears to have moved down relative to

the footwall block.

◗

Figure 10.15a).

Not all faults penetrate to the surface, but those that do

might show a

fault scarp

, a bluff or cliff formed by vertical

movement (Figure 10.15b). Fault scarps are usually quickly

eroded and obscured. When movement takes place on a fault

Search WWH ::

Custom Search