Travel Reference

In-Depth Information

Architecture

The sharp geographical contrast—it

could even be called a clash—between

British Columbia and the Prairies has

led to the development of two very dif-

ferent styles of architecture—as is true

of the other arts as well. The blanket of

forests and mountains that covers two

thirds of the Canadian West, combined

with the coastal climate, which is much

milder than in the rest of Canada, is

juxtaposed with the bare Prairies, where

the climatic conditions are among the

harshest in Canada, and the deep snow

is blown by violent winds during the

long winter months.

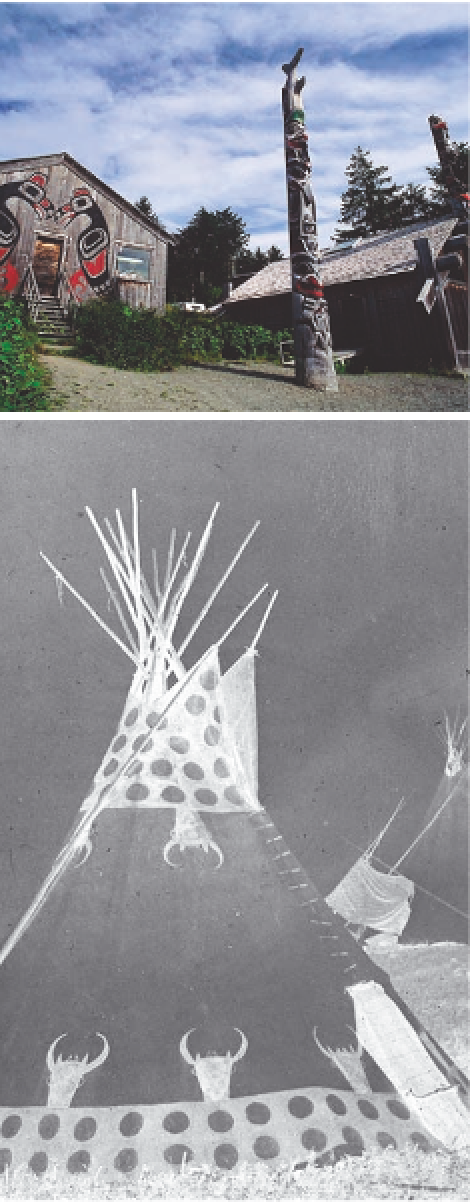

The Aboriginal people were the fi rst

to adapt to these two extremes. Some

developed a sedentary architecture

with openings looking out onto the sea

and the natural surroundings; others,

a nomadic architecture designed pri-

marily to keep out the cold and the

wind. Thanks to the mild climate along

the coast and the presence of various

kinds of wood that were easy to carve,

the Salish and the Haida were able to

erect complex and sophisticated struc-

tures. Their totem poles, set up in front

of long-houses made with the care-

fully squared trunks of red cedars, still

stood along the beaches of the Queen

Charlotte Islands near the end of the

19th century. These linear villages pro-

vided everyone with direct access to

the ocean's resources.

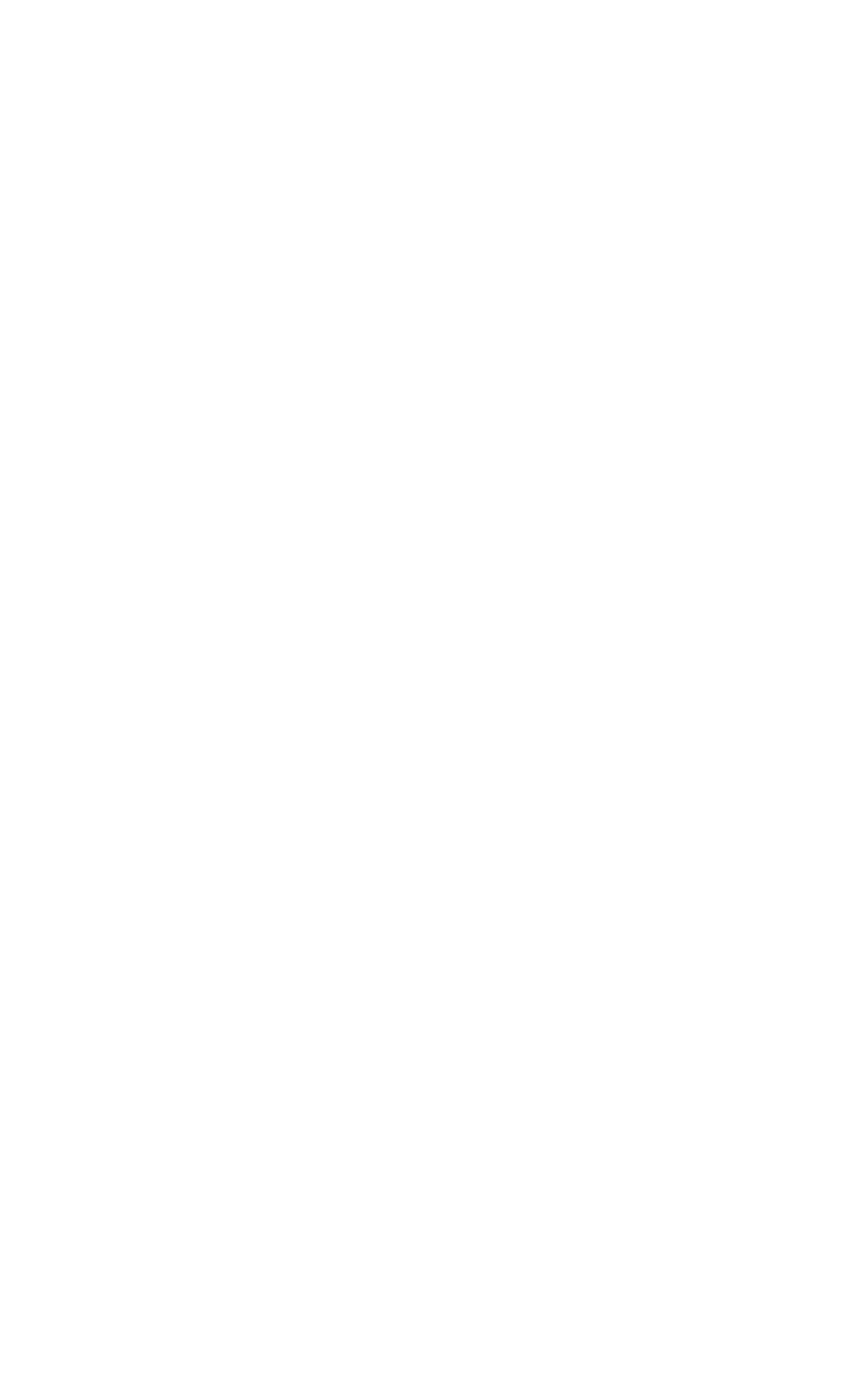

On the other side of the Rocky

Mountains, the Prairie peoples turned

the hides of bison to good account,

using them to make clothing, build

homes and even to make shields with

which to defend themselves. Their

homes, commonly known as tipis,

5

The reconstructed village of Ksan.

© Pierre Longnus

3

Tipis of the old plains.

© Glenbow Archives; NA-668-17

Previous pages

3

The pristine waters of a peaceful lake.

© iStockphoto.com / Vera Bogaerts

Search WWH ::

Custom Search