Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

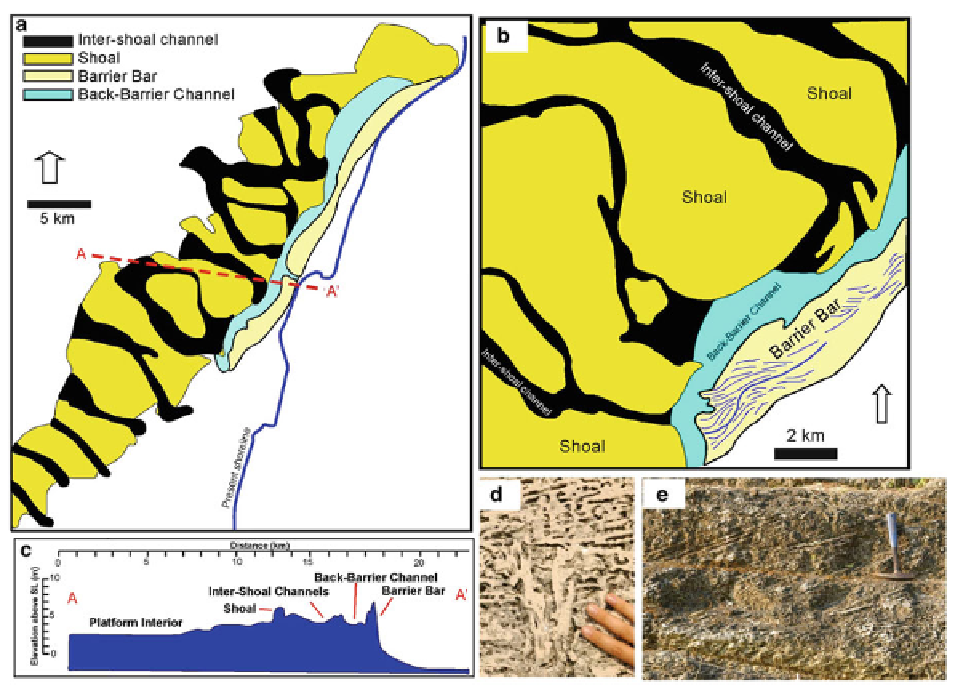

Fig. 20.18

Geomorphic patterns in an ancient ooid shoal com-

plex, Pleistocene Miami Oolite, Florida, modifi ed from Halley

et al. (

1977

) . (

a

) General facies patterns and dimensions of part

of the coastal ridge in the Miami area, and the paleogeomorphic

interpretations. (

b

) Detail of one area, illustrating the earlier

shoal and inter-shoal channels, and the later barrier bar.

(

c

) Representative topographic profi le across the bar system.

In terms of lateral and vertical scale, this system is broadly

comparable with the Joulter Cays system (cf. Fig.

20.17

).

(

d

) Downward-oriented, chevron-like anemone burrow cutting

through cross-bedding. (

e

) Preserved cross-bed sets, 30-40 cm

tall. Both sets are oriented in the same direction, as in many

systems, probably related to fl ood- or ebb-dominance in a spe-

cifi c location

porous, cross-laminated ooid-skeletal grainstone, and

eventually with another subaerial exposure surface and

paleosol (Ladore Shale). Overlying the paleosol is

another oolitic grainstone deposit (Mound Valley

Limestone) which has variable thickness, ranging from

3 m to absent, but is capped with another paleosol (the

Galesburg Shale). Comparable to Holocene examples,

this Upper Carboniferous example illustrates how

breaks in slope and subtle embayments that focus tidal

currents can be important factors infl uencing where

these bars occur. Similarly, the Mound Valley ooid

shoals stacked on the Bethany Falls high illustrate the

important role of subtle paleotopographic highs that

can focus tidal fl ows and favor formation of ooids.

Unlike Holocene examples, however, many ancient

systems have been extensively modifi ed by diagenesis.

For example, a well-sorted oolitic sand of a Holocene

accumulation may include abundant interparticle pore

space (Fig.

20.2e-g

). In many cases, the pore space is

partly fi lled by calcite or aragonite cement, of marine

(Fig.

20.3b, c

) or meteoric (Fig.

20.3h, i

) origin. The

aragonite that makes up the ooids is diagenetically

unstable, however, and a change in conditions (e.g.,

subaerial exposure and fl ow of meteoric fl uids through

the sand) may lead to partial or complete dissolution of

ooids, leaving behind molds of the former grains

(Fig.

20.21

). With progressive diagenesis, more grains

and even cements may be recrystallized (Fig.

20.21c,

d

). Clearly, the heartbreak of diagenesis can lead to

many diffi culties in trying to discern the details of the

geologic history or distribution of porosity and perme-

ability in ancient oolitic successions.