Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

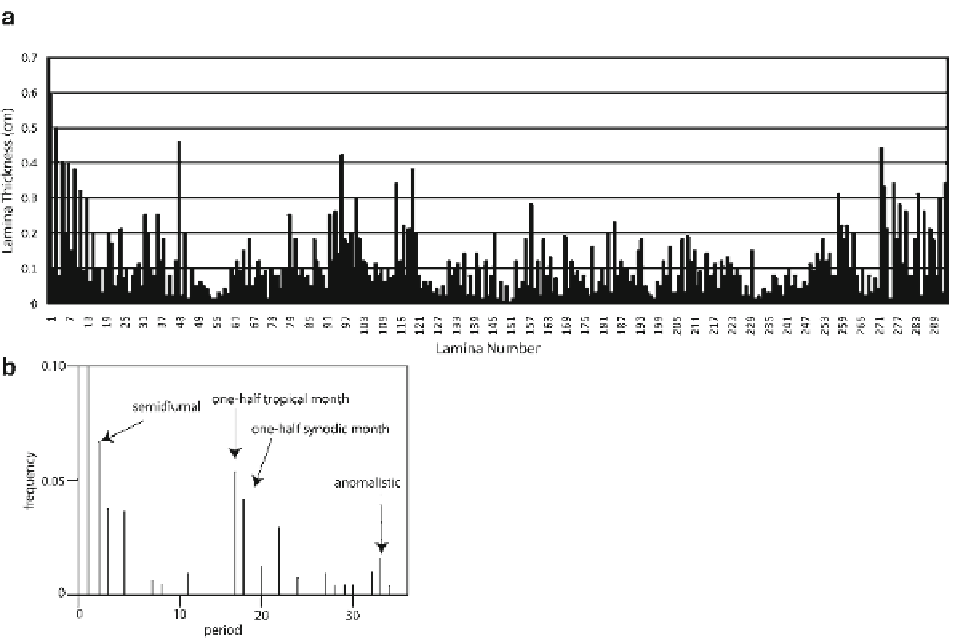

Fig. 14.14

(

a

) Lamina thickness versus lamina number for the

Cajiloa submarine canyon (see Fig.

14.11

). Notice the inequality

of the laminae thicknesses is quite pronounced, especially in the

beginning and end of the graph. (

b

) Fourier transform (power

spectrum) of the data from (

a

), with the semidiurnal, synodic

half-month, tropical half-month, and anomalistic periods high-

lighted. The presence of the other peaks may be indicative of

other currents or other tidal constituents

criteria, however, can be produced by turbidity currents

or contour currents (Kneller

1995

; Rebesco et al.

2008

), with the possible exception of a statistically-

signifi cant occurrence of thick-thin bundles (De Boer

et al.

1989

) and mud couplets

sensu

Visser (

1980

)

(Fig.

14.8

).

He et al. (

2008

) suggested that bidirectional cross-

lamintions or cross bedding, fl aser, wavy, and lenticu-

lar beds are normally observed in internal tide deposits.

Since all of these sedimentary structures can be pro-

duced in turbidity currents, however, they are not good

independent diagnostic criteria (Kneller

1995

) . He

et al. (

2008

) also suggested that there are characteris-

tic vertical successions in internal tide deposits, the

most recognizable being inverse to normal grading of

intervals (Fig.

14.7a, b, e

). While inverse to normal

grading undoubtedly occurs in tidalites, it can also be

a product of fl ood-generated turbidity currents

(hyperpycnal fl ows) or contour currents (Mulder et al.

2002

; Mulder et al.

2001

). If we look at what is genet-

ically unique to internal tidal currents, what stands out

is the cyclic nature of internal tides. Therefore, the

most convincing diagnostic criterion should refl ect

this cyclicity, either in statistically meaningful numbers

of thick-thin couplets or in repeated thickening-

thinning cycles, or both (Figs.

14.7

,

14.9

-

14.14

).

These cycles may be coupled with other criteria

that aid in the interpretation such as mud drapes or

couplets, reactivation surfaces, and bi- or multi-directional

cross-bedding, but without the evidence of cyclicity,

the other structures can as easily be explained by con-

tinuous or seasonal contour currents or by episodic

hyperpycnal or surge-type turbidity currents, which

after all can vary radically both spatially and tempo-

rally in energy and thus in erosion and deposition

(Kneller and McCaffrey

2003

) .