Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

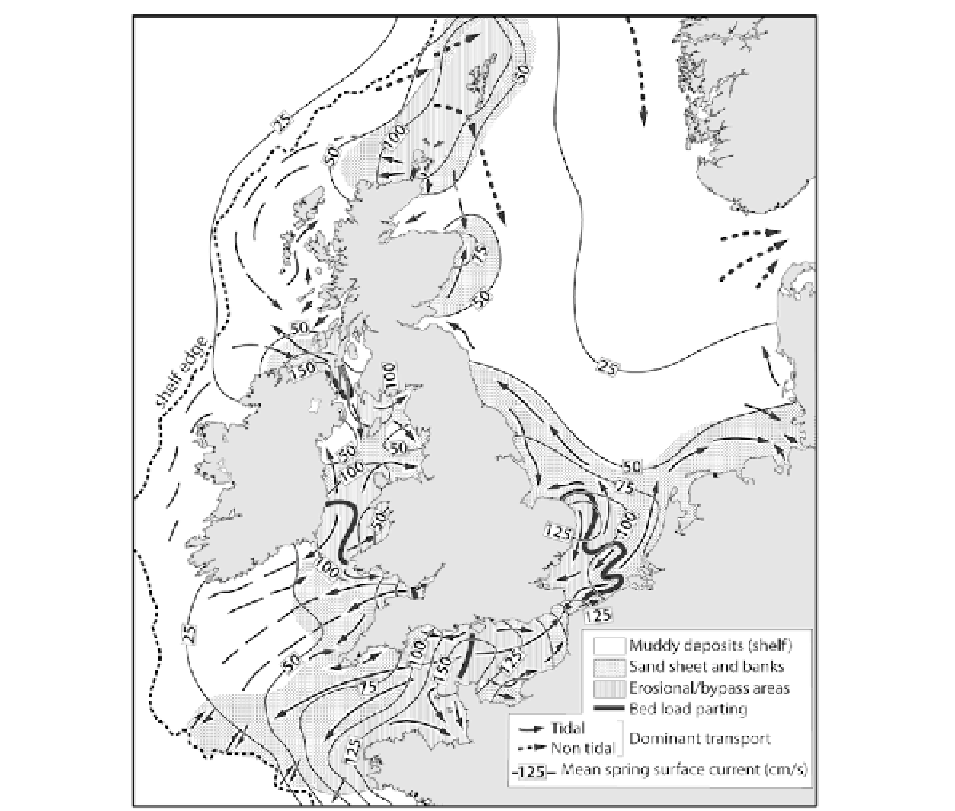

Fig. 13.16

Sea-floor sediment type, surface currents and tidal-

transport pathways around the British Isles. Arrows show poten-

tial bedload-transport directions that diverge from erosional

bedload partings, to convergence areas where deposition occurs

(After Howarth

1982

and Johnson et al.

1982

)

13.6.2 Bedform Distribution

direction of the residual transport begin to form. In

regions of limited sand, the dunes are separated by

areas with no sand cover (i.e., they are 'starved') and

have a barkhanoïd shape (Fig.

13.18b

). If there is a

larger amount of sand, the dunes coalesce to produce

tidal sand sheets (Fig.

13.18a

) and, under proper con-

ditions, tidal sand ridges (Fig.

13.18c

). At the extreme

end of the transport pathway, sheets and patches of

rippled fine and very fine sand occur where the current

speed is below the critical velocity for dune stability.

As discussed above, the upper limit on dune size

is controlled by the thickness of the boundary layer,

which is approximated by water depth in many situa-

tions. However, current speed, grain size and sediment

A predictable progression of bed features occurs along

a tidal-transport pathway as a result of changes in the

sediment regime (Belderson et al.

1982

; Fig.

13.18

). In

erosional, bedload-parting areas, older deposits are

exposed or are covered by a patchy veneer of lag gravel

and sand. Erosional features include current-parallel

furrows and flute-shaped depressions. Mobile sand in

these areas occurs as sand shadows in the lee of bed-

rock obstacles and as current-parallel sand ribbons.

Subaqueous dunes can be present on the sand ribbons.

As sand begins to become more abundant down the

transport pathway, fields of dunes that migrate in the