Biomedical Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

deficit states is not always apparent (3,46,48). But, social rewards may provide

insurance over time for satiating some motivational states, or avoiding aversive

outcomes (1,146) (Figure 4). Aversive events, in contrast, can be defined as

deficit states whose reduction could be considered rewarding (19). Along with

potential deficit states, rewarding and aversive outcomes also depend on valua-

tions and probability assessments of alternative payoffs that do not occur (i.e.,

counterfactual comparisons involving memory). As an example of a counterfac-

tual comparison (171), imagine that you and a friend saunter down a street. Both

of you simultaneously find money on opposite sides of the walkway, but she

finds a twenty dollar bill and you find a one dollar bill, resulting in you feeling

you were not very fortunate (Figure 3).

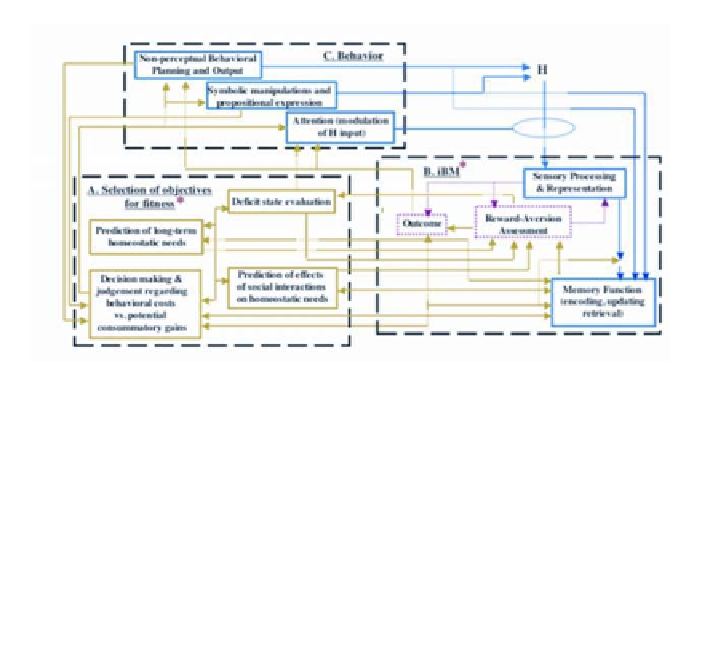

Figure 4

. The schematic of the Motivation Information Theoretic model is shown with compartment

lines represented by dashed black lines in bold. Compartments and connections in solid blue represent

processes and their interactions for which substantial neuroscience data has accumulated. Compart-

ments and interactions in light green are based on behavioral research and beginning neuroscience data

(1,46,99). Substantially less is known for them than for processes in solid blue. Purple dashes repre-

sent processes and interactions based on a body of neuroscience data, which is still far from the level

of knowledge currently available for the processes in solid blue. Stars are placed by the informational

backbone for motivation (iBM), and the operation for selection of objectives that optimize fitness over

time, to communicate a synthetic view that their processes comprise those that constitute the experi-

ence of emotion (65,67,129,146). See text for details. Figure adapted with permission from Breiter and

Gasic (32).

Objectives for optimizing fitness (Figures 2 and 3) focus on satiating both

short-term homeostatic needs and projected long-term needs through the insur-

ance provided by social interaction and planning (1). They represent multiple

motivational states, whose differing temporal demands produce complex dy-

namics between competing behavioral incentives. Darwin first recognized this

idea (67), and hypothesized that motivational states form the basis for emotion.