Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

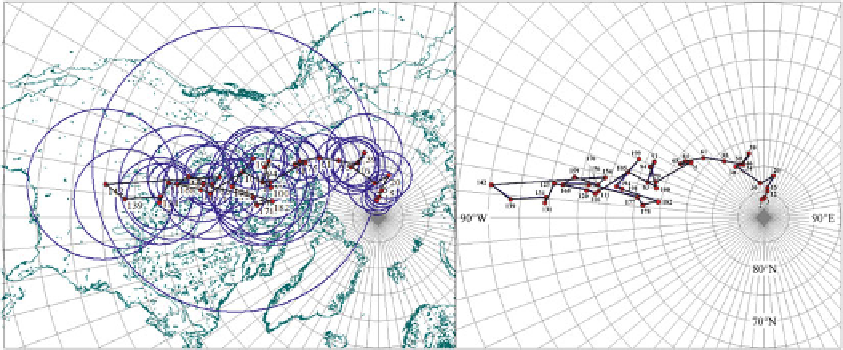

Fig. 6.10

A sliding-window APW path for the African

craton since 200 Ma (Besse and Courtillot

2002

), obtained

using a 10 Myrs window and 5 Myrs steps.

Blue circles

are

A

95

confidence cones (

left

).

Red dots

are mean paleopole

locations. The

right

pane shows more clearly the complex-

ity of this path, which includes several loops and hairpins

an APW path is a time series of

mean

paleopoles

p

(

t

1

),

p

(

t

2

), :::,

p

(

t

N

), where

t

1

<

t

2

<:::<

t

N

.

Therefore, a versor

p

(

t

i

) is always calculated

by a weighted averaging formula like (

6.55

).

Geometrically, the time series is represented by a

curve on the unit sphere, formed by a sequence

of great circle arcs linking the paleopoles. A

potential source of ambiguity in the construction

of these curves arises from the geomagnetic field

reversals. However, in paleomagnetic databases

like the GPMDB such ambiguity is overcome

by assigning to each listed paleopole a normal

polarity. Eventually, in the case of southern

hemisphere continents, it is possible to reverse all

the paleomagnetic poles and visualize the APW

paths as inverted polarity curves. The first APW

paths were built selecting groups of paleopoles

according to their

geologic

age. For example,

one could start determining the average of all

paleopoles having a stratigraphic or radiometric

age in the lower Cretaceous time interval,

obtaining the representative mean paleopole for

the lower Cretaceous. Then, the procedure was

repeated for the upper Cretaceous paleopoles,

and so on. This simple method was the only

possible approach when the number of available

paleopoles satisfying minimum reliability

criteria was small. Starting from the 1990s, the

publication of many new results allowed more

refined

Today, there are three general approaches to

the construction of APW paths. In the

sliding

window

method (e.g., Harrison and Lindh

1982

),

the paleomagnetic poles with ages falling within

a time window of fixed width (for example,

30 Myrs) are averaged to determine a mean

paleopole, which it is attributed an age equal

to the central age of the interval, or equal to

the mean age of the averaged paleopoles. Then,

the window is moved by an assigned step (for

example, 10 Myrs) and the procedure is repeated.

An example of sliding-window APW path is

shown in Fig.

6.10

.

A major problem with APW paths like that

illustrated in Fig.

6.10

is that they show a level of

detail higher than what is statistically justifiable.

This is quite evident by comparing the confidence

limits shown in Fig.

6.10

(left panel) with the

average distance between consecutive paleopoles

and with the hairpin turns of the path. There-

fore, it is likely that several consecutive mean

paleopoles of this APW path would pass a test

that establishes if two poles have been drawn

from a common distribution (e.g., McElhinny and

McFadden

2000

).

A second, more rigorous, approach to

the construction of APW paths consists into

the

selection

of

a

few

reliable

paleomag-

netic

poles

of

different

age,

without

apply-

analyses

of

the

paleomagnetic fields.

ing

time

averaging

(e.g., Gordon et al.

1984

;