Hardware Reference

In-Depth Information

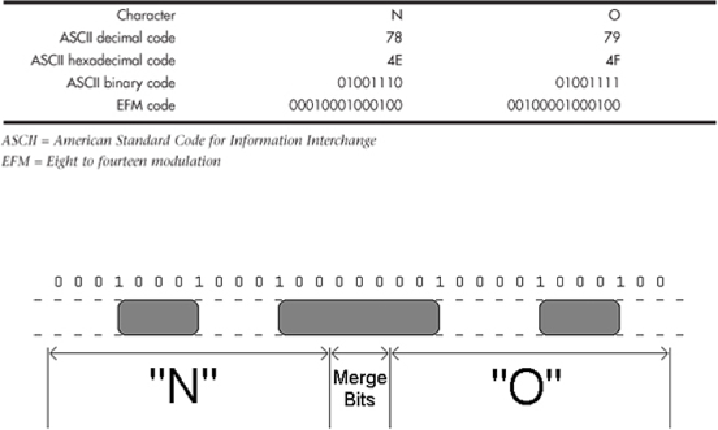

Figure 11.5

shows how the encoded data would actually appear as pits and lands stamped

into a CD.

Figure 11.5

EFM data physically represented as pits and lands on a CD.

The edges of the pits are translated into the binary 1 bits. As you can see, each 14-bit

grouping represents a byte of actual EFM-encoded data on the disc, and each 14-bit EFM

code is separated by three merge bits (all 0s in this example). The three pits produced by

this example are 4T (4 transitions), 8T, and 4T long. The string of 1s and 0s on the top of

the figure represents how the actual data would be read; note that a 1 is read wherever a

pit-to-land transition occurs. It is interesting to note that this drawing is actually to scale,

meaning the pits (raised bumps) would be about that long and wide relative to each other.

If you could use a microscope to view the disc, this is what the word “NO” would look

like as actually recorded.

Writable CDs

Optical disc recording has come a long way since 1988, when the first CD-R recording

system was introduced at the cost of $50,000 (back then, they used a $35,000 Yamaha au-

diorecordingdrivealongwiththousandsofdollarsofadditionalerrorcorrectionandother

circuitry for CD-ROM use), operated at 1x speed only, and was part of a subsystem that

wasthesizeofawashingmachine!Theblankdiscsalsocostabout$100each—compared

to less than 5 cents each in bulk cakebox form. (You provide your own jewel or slimline

cases.) Originally, the main purpose for CD recording was to produce prototype CDs that

could then be replicated via the standard stamping process.